Ambassadors to Achilles

As discussed in Derivation of Iliadic Self-Identity through Heroic Code, the men in Homer’s epic poem have a need to achieve immortality through their performance in battle, and that need haunts the entire story.

One important moment which stresses the outlook of men to be immortalized in song is in Book 9 when the ambassadors of Agamemnon visit Achilles, lines 223-239:

They found him there, delighting in his heart now,

Plucking strong and clear on the lyre—

Beautifully carved, its silver bridge set firm—

He won from the spoils when he razed Eetoin’s city.

Achilles was lifting his spirits with it now,

Singing the famous deeds of fighting heroes…

Across from him Patroclus sat alone, in silence,

Waiting for Aeacus’ son to finish with his song.

And on they came, with good Odysseus in the lead,

And the envoys stood before him. Achilles, startled,

Sprang to his feet, the lyre still in his hands,

Leaving the seat where he had sat in peace.

And seeing the men, Patroclus rose up too

As the famous runner called and waved them on:

“Welcome! Look, dear friends have come our way—

I must be sorely needed now—my dearest friends

In all the Achaean armies, even in my anger.”

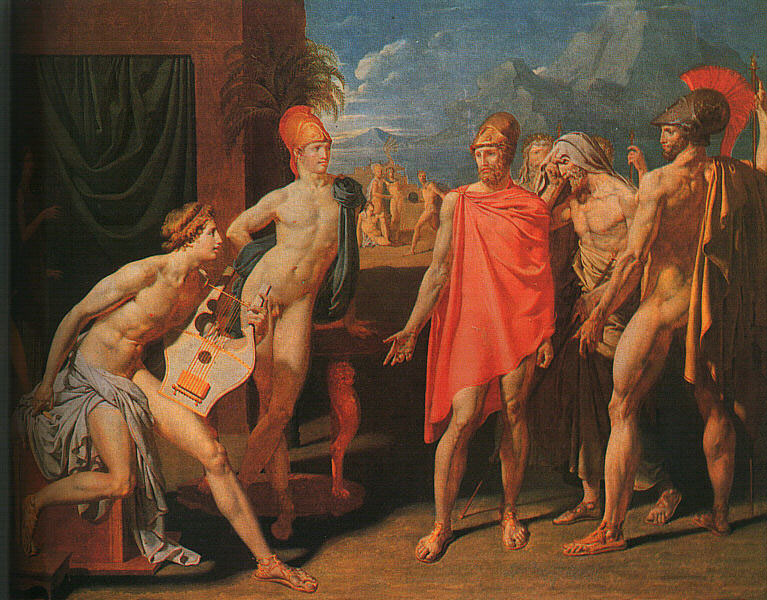

This moment is created visually by Jean Auguste-Dominique Ingres in a painting called “The Ambassadors to Agamemnon Visiting Achilles,” 1801. It is important because Achilles is seen with his lyre on the left side of the painting. He presumably was just “singing the famous deeds of fighting heroes” when the embassy arrived. The painting is able to capture the description given for the moment, but also it adds another layer to the imagery of the fighting hero.

The Ambassadors of Agamemnon Visiting Achilles, 1801

The general composition of the painting is as follows:

Both Achilles and his companion Patroclus display the languidly ephebic grace appropriate to noble bodies that have withdrawn from the fray…Patroclus, the transitional figure and the first to reenter the battle, playfully sports the helmet of Achilles, an anticipation of the disguise that will lead to his death at Hector’s hands. The entreating warriors, driven by the Trojan forces to the very brink of defeat, display the hardened musculature and indented contours of bodies marked in strife.” (Eisenman 51)

This visual manifestation of the text that is so rich in description says something about the magnitude of this moment. All of the focus is on Achilles because he is in the most active position. It sets him apart from the others physically and is compounded by the fact that he holds the lyre.

Achilles is different from the other men in the story of the Iliad because he chooses not to fight. “Achilles responds to his comrades’ pleas by rejecting the warrior’s way of life all together: he will go home and grow old in peace, abandoning the ‘’imperishable fame that will be his due if he accepts death at Troy.” (Clarke 82) There is a balance of power occurring at this moment in the painting to help emphasize the magnitude of Achilles’ decision. He is in a position to either accept or reject the offer made by the embassy.

Just by looking at the painting one can infer that he is in the power position, but it is not clear what he decides because Ingres has chosen to paint the initial meeting, not the decision. However, because Achilles has been represented as such a contrast to the other men prepared for battle, it can be inferred that Ingres has made Achilles appear to be enjoying his life away from battle.

The painting may represent only one moment in the story, but with that moment comes the task of relaying what has happened before and what is in these men to drive the story to what is next. Ingres is able to capture the tender relationship between Achilles and Patroclus by keeping them close to one another and making sure that they are set apart visually from the other men. It is clear who, at this point, is dear to Achilles. Therefore, it is only “After Hector kills Patroclus, (that) the internalized need for vengeance replaces Achilles’ socially determined need for honour; he must fight till he kills Hector, and if his own death is waiting straight after Hector’s, then so be it.” (Clarke 82)

This later part of the story will go back to what was said on the other page about the need to die honorably. Even though, in the painting by Ingres Achilles is shown to be somewhat peaceful and separate from the symbols of battle present on the other men, his rage sits underneath him. By putting him in a position where his is engaging with the other men, there is another layer to the action. Achilles is not simply sitting quietly and playing his lyre, something is going to happen and that is what Ingres is able to capture visually.

Finally, “For Homer as for Hesiod these warriors are… ‘the race of men who are half-gods…often by the literal fact of divine parentage but more generally because they stand at an intermediate stage between the gods’ infinite vitality and the sickly feebleness of modern man.” (Clarke 79) Both elements of infinite vitality and the feebleness of modern man are present in the painting. The infinite vitality is represented by the lyre, the instrument used to make men’s stories immortal. The modern man is represented in the helmets that the men wear to remind everyone of battle. And the idea of being a half-god is present in the men themselves who are at once connected and separate from the world around them.

For more information on Jean Auguste-Dominique Ingres visit:

http://humanitiesweb.org/human.php?s=g&p=c&a=b&ID=28

Bibliography:

Clarke, Michael. “Manhood and heroism.” The Cambridge Companion to

Homer. Ed. Robert Fowler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. 74-90.

Eisenman, Stephen F et al. Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History. Second Edition.

London, England: Thames and Hudson, 2002.

Homer. The Iliad. Trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin, 1990.