Environmental Justice Case Study: Navajo-Hopi Struggle to Protect the Big Mountain Reservation

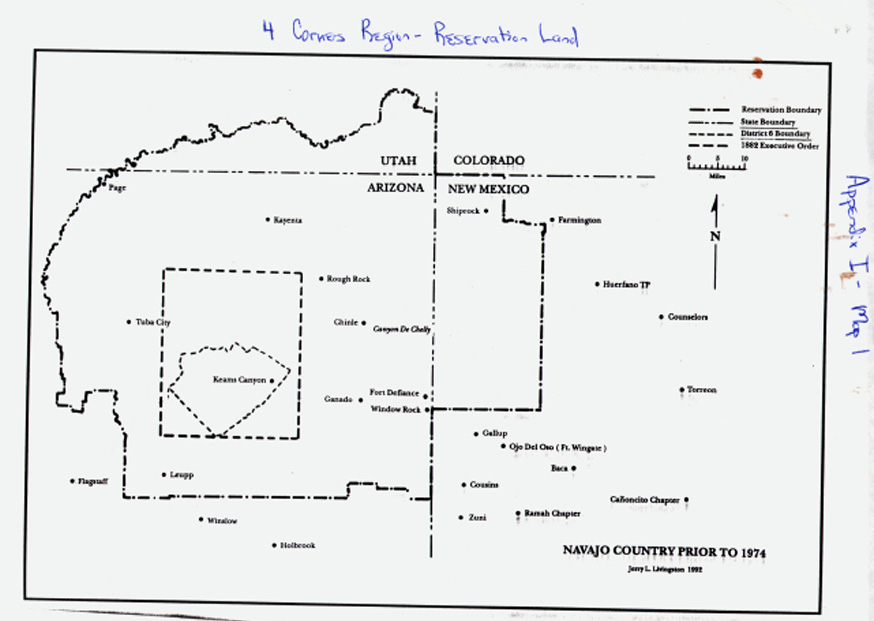

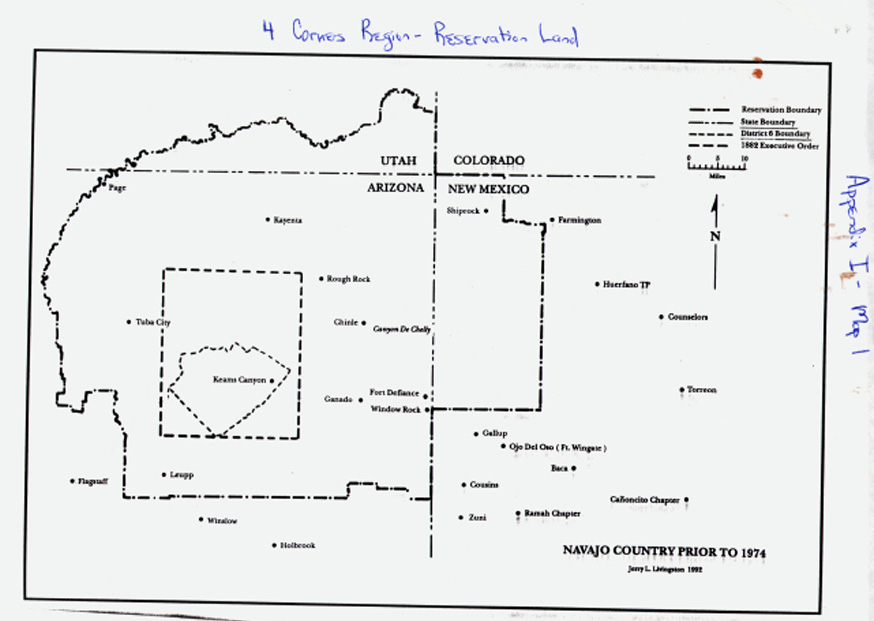

Above map taken from http://swcolo.org/Family/FourCornersMap.html, 1997.

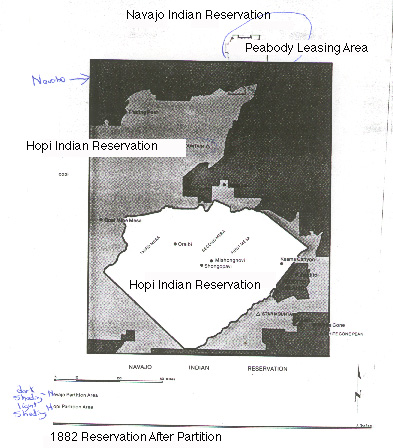

Above map taken from http://swcolo.org/Family/FourCornersMap.html, 1997.

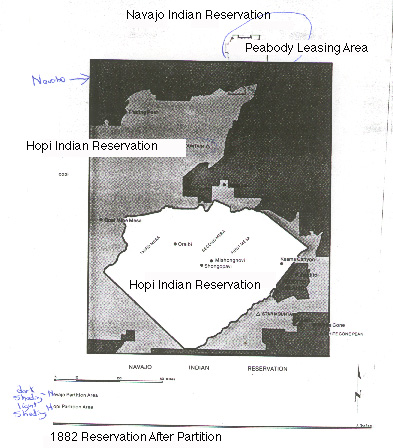

In 1974, the federal government partitioned the Big Mountain reservation, where the Hopi and Navajo tribes currently reside, and transferred some of the land to private ownership. Many Hopi and Navajo were relocated to other lands, but some 300 families remain at Big Mountain to fight the continued exploitation of their lands by private mining companies.

Currently, those 300 families are living on land that holds over $10 billion worth of coal. The Peabody Mining Company would like expand its operations by 13,800 acres, thus intruding upon the Big Mountain residents' sovereignty and potentially threatening the reservation environment. If Peabody is successful in gaining a federal permit to mine the reservation, the remaining 300 families face relocation.

Back to Table of Contents

The Hopi and Navajo have co-existed for generations in the American Southwest, long before Spanish or American explorers and settlers arrived. The Hopi are generally agriculturalists, and had settled in small villages. They are descendants of the Anasazi, the first Native Americans to occupy the area. The Navajo are pastoralists, and traditionally have lived in hogans distant from one another.

The concept of land owership is foreign to both tribes. In 1882, the United

States began a series of land boundary decisions which adversely affected the

natural resource rights of both tribes. As stated, the federal government partitioned

Hopi and Navajo reservation on Big Mountain in 1974, thus allowing private mining

companies to strip mine on or near these reservation lands. Many families were

relocated, and many more on Big Mountain still may face relocation as Peabody

Mining continues its efforts towards expanding its mining operations.

If Peabody is successful, the Navajo and Hopi lands will face water quality decline and depletion of water supply, devastation of the landscape, and desecration of sacred lands. Coal is transported in water slurry pipeline more than two hundred miles to a power station in Nevada. Water is in short supply in semi-arid regions, and using it for the transportation of coal depletes the water supply dramatically. This can in turn disrupt the fragile hydrologic cycle. Further, a lack of water can make agricultural and livestock production nearly impossible for both tribes. Also, sacred areas would be torn apart by strip-mining or altered by decreased water supplies. An Environmental Impact Statement addressed the cultural effects of land degradation on Big Mountain Reservation, and stated that the effects "could be mitigated through careful consultation with tribal members and payment for spiritual ceremonies on sites that will be destroyed" (Bullard, 1994). This is clearly insufficient, as there is no market value that can be placed on spiritual ceremonies, and the statement lacks any sensitivity or respect for Hopi-Navajo culture.

The relocation site that has been selected by the federal government has its own environmental problems. This site is near Sanders, Arizona where 100 million gallons of uranium-contaminated water broached a dam and spilled into the surrounding area.

Back to Table of Contents

Goverment Agencies

Goverment Agencies

Several government agencies are currently involved in this conflict. They include the Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation Effects (OSMRE), the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Department of the Interior, and the state of Arizona. In part, the position of these agencies is to promote development in the West and expansion of coal mining operations.

Peabody Coal Mining Company

Peabody Coal Mining Company

Peabody is a multi-national corporation, and is currently interested in expanding its mining operations onto Hopi and Navajo reservation lands.

Tribal Councils

Tribal Councils

The tribal council system is the only formally recognized representative of the Native American community by the state and federal governments. The council makes all decisions regarding the natural resource base of the reservation. However, tribal councils do not always represent the interests of the community on the reservation, and often have much to gain financially when coal mining operations expand onto Navajo and Hopi lands.

Traditional Tribal Members

Traditional Tribal Members

There are many members of the Hopi and Navajo communities that wish to preserve their cultural integrity, and prevent the destruction of their native lands. They hold that Americans have no understanding of what it means to belong to the land, rather than own it. They simply desire to left alone by Peabody, the Tribal Councils, the federal government, and the state of Arizona.

Back to Table of Contents

The map in Appendix I shows the general region and location of the Four Corners area of the American Southwest. The second map in Appendix II is a closer look at the area of interest. (Click here to see both appendices). One can notice the proximity of the Peabody leasing area to the Big Mountain reservation, where 300 families currently reside. Many of them are elders, and have no electricity, heat, or running water. They live in family hogans, and subsist on farming, herding, and weaving.

Back to Table of Contents

Several strategies have been employed by the Hopi and Navajo on Big Mountain to prevent Peabody's mining expansion onto their lands. Navajo elders have engaged in non-violent civil disobedience. They have placed their bodies in front of bulldozers, torn-down fences, and turned away government officials. Also, there has been a great deal of effort by the elders to increase community awareness and involvement in the struggle to preserve and protect their lands. Building sites on the internet has been a valuable tool in keeping the community informed, as well as frequently holding meetings to discuss tactics and strategies. They have staged letter writing campaigns, email campaigns, and engaged in other forms of lobbying. Also, they have pushed delegates of the Navajo nation in D.C. to prevent the expansion of Peabody's operations.

The Navajo have also filed several lawsuits concerning land use and water

rights, claiming that Peabody has infringed upon Navajo rights to water on reservation

land. Other lawsuits have addressed the Navajos' inability to perform religious

ceremonies and other practices due to destruction of the land. Land dispute

lawsuits began in 1958 and continue to the present. On March 11, 1996 federal

judge Ramon Child ordered the cancellation of Peabody's mining permit. According

to Native American Support Group, Judge Child "pinpointed the cozy relationship

between the mining companies, the tribal councils, the OSMRE and BIA and the

complete disregard for human and environmental rights of the local residents."

The mine remains open as Peabody appeals.

Back to Table of Contents

The current definition of environmental justice is "the right to a clean and safe environment in which to live, work, and play" (Bullard, 1994). That definition might be expanded to include the right to preserve one's cultural integrity, and to free from techno-environmental changes that inhibit such preservation. Unfortunately, none of the current tactics have ensured this right. Although Judge Child's ruling has prevented Peabody from mining on Hopi-Navajo reservation lands, there is still a chance that Peabody's appeal will be successful, and thus allow them to expand their operations.

Back to Table of Contents

Co-management of natural resources, and the conflicts that emerge from defining rights to their use, is a highly recommended approach to resolving the Hopi-Navajo struggle. The Hopi and Navajo communities must be empowered to participate in decisions which directly influence them. For example, the Hopi and Navajo communities should be allowed to participate in a more thorough social and environmental impact assessment that will reflect the interests of not only Peabody and the federal and state governments, but also the Hopi and Navajo. This will foster a more complete understanding of interests between parties, and potentially provide an acceptable resolution.

Back to Table of Contents

Contacts

John Burrows, Director

The Center for World Indigenous Studies

c/o The Fourth World Documentation Project

P.O. Box 2574

Olympia, WA 98507-2574

email: jburrows@halcyon.com

Sovereign Dineh Nation

P.O. Box 40319

Flagstaff, AZ 86004

email: sdn@primenet.com

Or click here to visit the

website.

Works Cited

Brugge, David. 1994. The Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute: An American Tragedy. Albuquerqe, N.M.: University of New Mexico Press.

Kramer, Jerry. 1980. The Second Long Walk. Albuquerque, N.M: University of New Mexico Press.

Bullard, Robert D. (ed.) 1994. Unequal Protection: Environmental Justice

and Communities of Color. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Back to Table of Contents

Goverment Agencies

Goverment Agencies

Goverment Agencies

Goverment Agencies Peabody Coal Mining Company

Peabody Coal Mining Company Tribal Councils

Tribal Councils Traditional Tribal Members

Traditional Tribal Members