|

|

After the stock market crash of 1929 city and state government laws were passed to restrict employment opportunities to U.S. citizens only. The federal government required that all firms supplying goods or services were to hire only U.S. citizens. General Motors in New York was the first major company to discharge all its alien employees. Jobs in the Works Progress Administration, under the New Deal, only allowed aliens to work if they were WWI veterans. Other exceptions were made for the spouses of U.S. citizens and veterans who served in the armed forces of U.S. allies. The U.S. government made welfare recipients work in Civil Work projects, however, those who were not eligible could receive more welfare. This created tension between groups because many considered it unfair that Mexicans received more welfare by default.

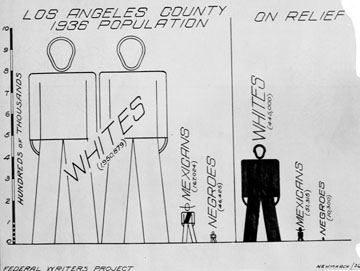

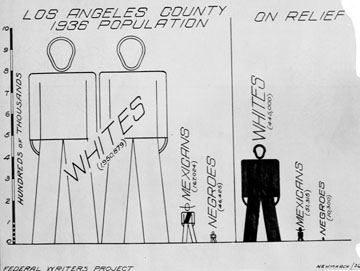

In 1937 The New York Times reported that two million of the 2.5 million Mexicans in the U.S. were unemployed and most of Chicago’s Mexican population—estimated at 25,000—headed back to Mexico or to the Southwest in search of jobs, which left less than 5,000 remaining.1 In the western U.S. competition for already scarce jobs intensified. For example the L.A. County Board encouraged companies to only hire locals. Mexican communities formed groups that petitioned the Mexican government for assistance but were unsuccessful. Many preferred returning to Mexico to receiving welfare aid. The problem went out of control and in 1931 Los Angeles’ welfare rolls increased from 3,500 people to 35,000 families.2 Los Angeles County replaced its Department of Charities leadership and later used it as a blueprint for federal the welfare system. The system, however, was not fair and Mexican families received much less in assistance because they were thought to have a lower standard of living. Contrary to popular belief that most Mexicans were on welfare during the depression the chart above disputes this notion. The proportion of Mexicans receiving aid in L.A. county was significantly less than that of whites. Furthermore, in Cook County (Chicago) only 0.8 percent of recipients were ‘Mexican and others’.3 An increasing number of layoffs put more pressure on the major cities to support the unemployed. As a result, large budget deficits became commonplace. Mexicans requiring assistance faced discrimination in many ways; for example, legal residents were told that citizenship was required to receive assistance. Still, other cities, like Los Angeles, were more generous in their monthly payments to the needy. Los Angeles police also established an illegal post in their Arizona-California border to keep indigents from applying for assistance.

The most vocal group to oppose giving assistance to aliens was the National Club of America for Americans which requested that the government prohibit appropriation of public money for feeding, caring for, or giving jobs to aliens. This group conducted surveys for extended periods of time to see how much money Los Angeles and the state had spent on welfare in an effort to mis-educate the public and raise support for their ideas. Other misinformed and/or racist groups expressed widespread support for these welfare reform ideas. Cities like Los Angeles and New York required proof of legal entry before receiving assistance, which made many inelligable for such programs. The use of inaccurate statistics about the numbers of Mexicans on welfare by U.S. officials in Mexico created tension between both countries.

Public officials who thought that many Mexicans gave up their health in helping the U.S. and its economy and therefore they should not be repatriated. In many instances illegal practices were used to encourage voluntary repatriation. For example, one Mexican-American woman opted for returning to Mexico because her husband was kept in jail and about to be deported. A program was started on December 1941 to offer some months’ worth of assistance to Mexicans if they returned to Mexico.4

Return to History Page |