|

|

last modified: Sunday, December 4, 2005 10:06 PM |

|

The Rouge: Yesterday, Today, & Tomorrow |

|

Lindsay-Jean Hard |

lgilreat@umich.edu |

Initially, what was to become the River Rouge Plant began in 1915 as nothing more than 2000 acres of land along the Rouge River. Ford acquired the land without a particular use in mind. In fact, car production did not begin until 1927, what it is known for today. Initially the plant was first used to produce Eagle Boats (warships designed to chase down submarines) and then tractors. [3] The first automobile produced at the plant was the new Model A, and as Henry Ford was building his industry, his son Edsel was busy presenting and promoting his father’s vision to the nation. [4] A 1.3 million dollar advertising campaign was launched to “generate excitement and public interest in a new modern automobile and powerful new plant.” [5] One aspect of this campaign was to commission photographer Charles Sheeler to capture the essence of the factory. Sheeler produced less than 40 photographs during his time at the Rouge, but the series is considered his most critically acclaimed, and furthermore, is regarded as the high point of industrial-era photography. [6]

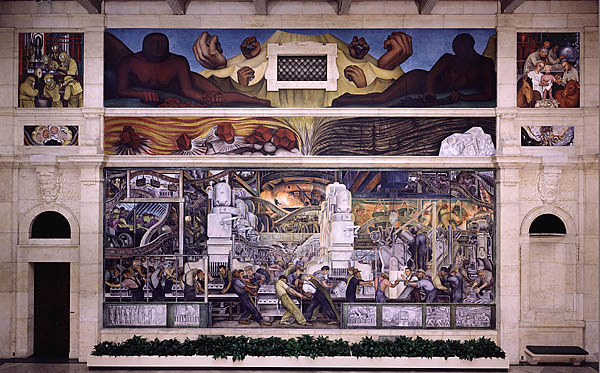

Diego Rivera was the next artist Edsel pursued in order to promote the family business as well as “…glorify the industrial renaissance.” [7] Rivera hoped to capture more than that though. He felt that his work should “…glorify the dignity of the workers.” [8] For eight months, beginning in 1932, Rivera painted elaborate frescoes on the walls circling the Detroit Institute of Arts’ Garden Court. As suggested from the view of the museum’s North Wall below, Rivera captured and expressed many different relationships and ideas in these frescoes. Rivera presented “themes of dependence on the resources of the land and the evolution of technology,” while he captured the many different races in the workforce of America. [9] Unknowingly, Rivera’s image below foreshowed the future labor struggles Ford faced due to the River Rouge Plant’s hot, cramped and sometimes unsafe conditions.

Photo courtesy of: www.dia.org/education/rivera/info9.htm

The River Rouge Plant was an “ore to assembly” complex, designed to achieve Ford’s ground-breaking goal of complete self-sufficiency. [10] Ford wanted to attain a “continuous, nonstop process from raw material to finished product, with no pause even for warehousing or storage.” [11] To reach this end, Ford owned coal mines, iron mines, limestone quarries, acres of forest, a rubber plantation, and even an entire regional railroad company. In 1920, Ford put a power plant into operation that supplied the Rouge with all of the electricity it needed. Sometimes Ford was even able to sell surplus power to Detroit Edison Company. Three years later, Ford had a glass plant built. This plant produced a higher quality of glass for a reduced cost, due to a new process that Ford himself helped to create. He was obsessed with reducing costs, and used efficiency studies to try and constantly improve production. [12] Ford intended to make owning an automobile accessible to the masses, and in order to do that, he had to bring down the cost. He was able to do this by being the first to successfully implement the assembly line on a large scale, bringing the work to the working instead of the other way around. Ford Motor Company was able to produce cars at a much faster rate, and thus lower the cost of the automobile. The institution of mass production, “Fordism,” was born. [13]

Improving production, at least initially, also corresponded with improving the lives of his workers. In 1914, Ford essentially doubled the going pay rate; he offered a $5 work day, and reduced the standard work day from nine to eight hours. [14] This unprecedented wage policy “helped transform American society by expanding the country's middle class and creating opportunities for minorities and immigrants who rushed to Detroit for lucrative auto jobs.” [15] And then, by 1926, Ford was paying his workers six days pay for five days of work. This was not pure generosity though; Ford was truly building an empire. Ford realized that the better his workers were paid, and the more leisure time they had, the more likely they were to spend their money…on one of his cars. As he said, “A workman would have little use for an automobile if he had to be in the shops from dawn until dusk.” [16] Ford did not just rapidly expand America’s middle class, he helped to create the society of mass consumption that we have today. People were drawn from all over the United States, even the world, enticed by the prospect of a new lifestyle Ford was providing. [17]

During

the 1930s, in the height of the plant’s production, Ford employed over

100,000 workers.

[18]

This began to change though after Ford’s

death in 1947, as Henry Ford’s grandson, Henry Ford II had to adapt

to a changing economic atmosphere, requiring decentralization and globalization. Concern

for the environment was also increasing, and air, water, and emissions standards

began to be developed. As Ford

began to pare down the number of industries it was involved in, and began

to rely on an increasing number of suppliers, the number of operations and

jobs at the plant declined. This

was only one of the many hurdles the Rouge faced and overcame along the way. Another was a famous labor strike in

1937, which ultimately led to unionization of the plant’s workers. Then in 1973, Ford Motor Company—and the rest of the

nation—was hit by OPEC’s oil embargo, which drastically raised

the price of gasoline and limited production at the Rouge. By 1992, only one car was still being built at the Rouge,

the Mustang, but the workers pulled together once again. The UAW together with the company

helped create a second chance for the Rouge, by creating a new operating

agreement, investing in modern equipment, and reintroducing the Mustang. Extensive renovation and modernization

helped the company start to make a comeback by the late 1990s.

[19]

Now known as the Ford Rouge Center, the 600 acre complex currently produces the new Ford F-150s and employs about 6,000 workers. While this is a significant decrease from the glory days of the River Rouge Plant, Bill Ford is attempting to produce a comeback for the plant. Ford realizes that depleting natural resources is a growing concern for people all around the world, and hopes to prove that manufacturing processes can hold to an environmental standard and still be profitable. The revitalization effort balances “the needs of auto manufacturing with social and environmental concerns,” all while reducing costs, presumably just as the original Ford would have wanted. [20]

The new Ford Rouge Center is focused on sustainable manufacturing, or “high-performance design.” [21] This facility has the capability of producing various types of automobiles—using fewer types of base platforms—a money-saving approach that is much more flexible than Ford’s original assembly line. The plant also uses just-in-time production, so parts and materials are delivered as needed, potentially reducing waste and overstock. The Ford Rouge Center is also very environmentally focused, it has the world’s largest porous parking lot and over 10 acres of roof covered with sedum, a living plant, two parts of an extensive system to manage storm water naturally. The assembly plant has new energy efficient skylights, which reduce glare and heat; this requires less artificial light to be used, and reduces electrical energy usage. These are just a couple of the modifications designed to “lower annual energy costs, lower long-term maintenance costs, create healthier work environments, improve employee productivity, help protect the environment, and improve market image.” [22] Of course, Ford’s critics might question how he reconciles that despite the wash of green, Ford is still producing vehicles, inherently environmentally unsustainable goods. However, Ford Motor Company is going beyond producing an environmentally friendly plant; they are working on fuel cells, hybrid-technology, and hydrogen based transportation systems. [23] Moreover, Ford—like his great-grandfather—is focused on innovation. In order to weather the harsh automotive climate, Ford is leaning on the same thing that drove his great-grandfather to build an empire – innovation. Ford is providing a product to his customers, but is using innovative technology to make the automobile more sustainable, while producing it in a more sociable and environmentally-conscience manner. Ideally these changes will renew the Ford legacy and as Bill Ford hopes, allow the Rouge to once again be an innovative complex, producing competitive products and creating new economic standards.

[1] The Henry Ford: Ford Rouge Factory Tour. 2005. “History of the Rouge.” Accessed on 10/10/ 2005. http://www.thehenryford.org/rouge/history.asp

[2] Ford, William C. The Henry Ford Museum. The River Rouge Plant, Observation Deck. Visited on 10/9/2005.

[3] The Henry Ford: Ford Rouge Factory Tour. 2005. “History of the Rouge.” Accessed on 10/10/2005. http://www.thehenryford.org/rouge/history.asp

[4] Baulch, Vivian and Zacharias, Patricia. The Detroit News. 12/19/2002. “The Rouge Plant – the Art of Industry.” http://info.detnews.com/history/story/index.cfm?id=189&category=business

[6] Ibid.

[7] Baulch, Vivian and Zacharias, Patricia. The Detroit News. 12/19/2002. “The Rouge Plant – the Art of Industry.” http://info.detnews.com/history/story/index.cfm?id=189&category=business

[8] Ibid.

[9] Downs, Linda. 1994. Detroit Institute of Arts gallery guide, “The Detroit Industry Frescos.”

[10] The Henry Ford: Ford Rouge Factory Tour. 2005. “History of the Rouge.” Accessed on 10/10/2005. http://www.thehenryford.org/rouge/history.asp

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] PBS. A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries. 1998. “Ford Installs First Moving Assembly Line.” Accessed on 10/10/2005. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dt13as.html

[14] Garsten, Ed. The Detroit News. 6/9/2003. “Ford’s $5 Day Altered America.” Accessed on 10/23/2005. http://www.detnews.com/2003/specialreport/0306/09/f10-186947.htm

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] The Henry Ford: Ford Rouge Factory Tour. 2005. “History of the Rouge.” Accessed on 10/10/2005. http://www.thehenryford.org/rouge/history.asp

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ford Motor Company. 2005. “Innovation: Engine & Fuel Technology.” Accessed on 11/21/2005. http://www.ford.com/en/innovation/engineFuelTechnology/default.htm