Factory Woman

So it is your curiosity that brought you to the factories of Chicago in the early 1900's. Well now that you are here, you probably want to know what it was like to spend a day in a Chicago-style factory from a woman's perspective. Since you have already seen the factories through the eyes of Carrie, you might think that she was nothing more than a wimp and an over exaggerator. After all, she was able to handle no more than one day in the factory. However, after you finish reading you might have to reevaluate whether or not you could handle a day in the life of a factory woman.

So here you are in the factories, or what many considered to be breeding grounds of sin and corruption. It was this stigma associated with the factory that caused many fathers to hesitate before sending their young daughters to work here. However, if you take a look around, the average age of the women here is between 17 and 22 years. Since the women in the factories were so young, it was often thought that they were unable to prevent themselves from falling into a life of sin and corruption. Therefore, to stop these young factory women from losing their innocence, they were commonly under the watch of a matron who was usually a middle-aged widow (5). The matron was the one who made sure that each girl was in proper attendance and was keeping up with the work demanded of her. Often factories required that girls use religious worship on a regular basis as a way of retaining purity of the soul (5). By obliging the girls to participate in such activities, the factories underhandedly alleviated some of the family's fears of sin and corruption that were usually associated with the factories. Thus, the strict watch that some women endured in the factories was just one of the reasons that their working conditions were nowhere near as free as those of men's.

Also, as you take a look around, you might notice that factory women, or “shopgirls,” stood out like sore thumbs in society because of their appearance. “In the case of females . . . Wages were set at a level which would be high enough to induce young women to leave the farms and stay away from competing employment . . . but low enough to offer an advantage for employing females rather than males” (5). Since the women did not invest in their appearance, they often wore dresses made from material that was sometimes so worn out that the garments resembled rags. In the book Sister Carrie, Carrie herself noticed that when she was better dressed, she got more respect from the shopkeepers and managers when applying for jobs. Also, after Carrie left her job at the factory and decided to take Drouet up on his offer to buy her new clothes, she was “upgraded” into a different social class (4). This upgrade was based on a materialistic level because she now physically resembled the women of the middle class. Also, when Carrie was walking with Drouet and saw the factory girls that she had worked with, she felt no need to recognize their presence because they now were of a different class than Carrie. It was not uncommon at this time for vanity to speak louder than all else.

Even when these women reached a point where they had enough money to buy nicer clothes, they would rather spend it on finery, save it for the future, or give it to their families on the farms. One of Dreiser's continuing themes throughout his book deals with physical appearance because the author strongly emphasizes his characters' dress and looks. Even though he is mostly focused on the metamorphosis of Carrie's physical appearance, he often comments on Mr.Hurstwood and Drouet's fine clothing as well. “Hurstwood's shoes were of soft black calf, polished to a dull shine, while Drouet wore patent leather . . . [Carrie] noticed these things almost unconsciously”(4). Dreiser's descriptions of appearances are so detailed - even with the men - that he truly gives the reader a sense of how important appearance was in society at the time. Noticing clothes and appearance became a second nature, falling into the subconscious and becoming so natural that one does not even realize its being done.

On the other hand, Dreiser commences the book with a short and simple description of Caroline Meeber. Even though she is a natural beauty, her unrefined appearance was not so appealing to the eye. However, as soon as Carrie meets Drouet and he offers to fix her up a bit, she quickly falls into the temptation of looking like all the other middle class women. “That evening Drouet found her dressing herself before the glass. 'Cad,' said he, catching her, 'I believe you are getting vain.' [Carrie replied] 'Nothing of the kind,' she retorted smiling"(4). The factory girls were not well accepted in the high society of Chicago because it took only one look to figure out that they were working women.

“Carrie got so at last that she could scarcely sit still. Her legs began to tire and she felt as if she would give anything to get up and stretch. Would noon never come?... Her hands began to ache at the wrists and then in the fingers, and toward the last she seemed one mass of dull complaining muscles, fixed in an eternal position and performing a single mechanical movement which became more and more distasteful until at last it was absolutely nauseating (4).”

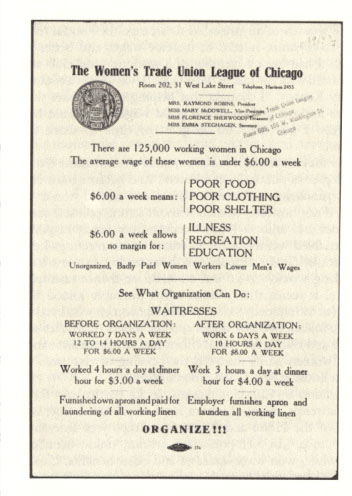

Similarly, it was not only the physical appearance of the factory girls that needed a bit of upkeep. If you take a look around it is more than obvious that the factories themselves were breeding places of disease and infection. The girls' immunity to disease and infection was greatly reduced due to the overexertion they subjected their bodies too. In the busy seasons, the girls sat in front of their sewing machines for over ten hours per day, working as fast as they could to keep up with the high demand (2). “The girls became victims of consumption, dyspepsia, and life-long pelvic disorders. These are the results of the overexertion, bad housing, undernourishment and noxious surroundings common to their calling and condition in life (2).” As Dreiser clearly illustrated in Sister Carrie, the working conditions were so bad that Carrie decided she could handle no more than one day in the life of a shopgirl. The sweatshops were often much worse than the factories themselves because they were usually residences that were transformed into small garment producing warehouses (2). It was not uncommon to find a family member with a terminal illness in contact with, or in very close proximity to, the newly produced garments. “In a tenement house a man was found just recovering from malignant diphtheria, while in the room adjoining, on the same floor, and in the room above, knee-pants were being finished, and the work had not been suspended during any stage of the disease” (2). Due to the combination of low salaries and lack of health precautions taken by the employers, when women did fall sick they often times did not seek medical attention because it was merely too expensive. Also, time in bed meant time away from the job, and since a loss of income was out of the question for some women, many diseases were left untreated.

Now that you have seen the physical, societal, and mental stress that the women in the factories were often subject to, do you think all that would be worth a mere few dollars a week? Even though Carrie always seemed to be searching for the easy way out and never was satisfied with what she had, her experience in the factory did not seem too far from the reality of the situation in the early 1900's.