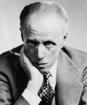

Sinclair Lewis

The Life of Sinclair Lewis

Born in 1886, in Sauk Centre, Minnesota, Henry Sinclair Lewis became the first

American novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. The son of a country

doctor, from a family of three boys, he grew up introverted and intelligent

in this town with a population of 2,800, most of which was Swedish and Norwegian.

At the age of 17 he broke free of the mid-west, entering Yale, and from there

he worked unsuccessfully in publishing for several years. In his spare time

he wrote, and after producing five novels, all of which went unnoticed, he

became a household name with Main Street in late 1920. After this

publication, he had several consecutive successes: Babbitt (1922),

Arrowsmith (1925), Mantrap (1926), Elmer Gantry

(1927), The Man Who Knew Coolidge (1928), and Dodsworth

(1929) were all well received. In 1926 Lewis was to be awarded the Pulitzer

Prize for his novel Arrowsmith, but refused. Four years later, however,

he accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Once he began writing, Lewis also traveled a great deal. Though much of his time was spent abroad, he continued to write about the people and towns of his homeland. This excerpt taken from an autobiographical sketch submitted to the Nobel Prize committee details his feelings on the United States:

I have travelled much; on the surface it would seem that one who during these fifteen years had been in forty states of the United States, in Canada, Mexico, England, Scotland, France, Italy, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Jugoslavia, Greece, Switzerland, Spain, the West Indies, Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Poland, and Russia must have been adventurous. That, however, would be a typical error of biography. The fact is that my foreign travelling has been a quite uninspired recreation, a flight from reality. My real travelling has been sitting in Pullman smoking cars, in a Minnesota village, on a Vermont farm, in a hotel in Kansas City or Savannah, listening to the normal daily drone of what are to me the most fascinating and exotic people in the world - the Average Citizens of the United States, with their friendliness to strangers and their rough teasing, their passion for material advancement and their shy idealism, their interest in all the world and their boastful provincialism - the intricate complexities which an American novelist is privileged to portray.

The Writing Style of Sinclair Lewis

Besides

being the first American author to win the Nobel Prize in literature, Sinclair

Lewis had a writing style that was considered revolutionary. In 1920, the

publication year of Main Street, the United States was still feeling

the effects of World War I. Glorified both internationally and within the

country, Americans were seen as ideal citizens from a superior land. Lewis

took a daring stand, and his work brought about the deconstruction of the

myth regarding small-town America.

Besides

being the first American author to win the Nobel Prize in literature, Sinclair

Lewis had a writing style that was considered revolutionary. In 1920, the

publication year of Main Street, the United States was still feeling

the effects of World War I. Glorified both internationally and within the

country, Americans were seen as ideal citizens from a superior land. Lewis

took a daring stand, and his work brought about the deconstruction of the

myth regarding small-town America.

Within our class, we have discussed Main Street (1920) and the movie Elmer Gantry (1960), based on Lewis’s book by the same title (1927). Both of these focused on its setting: the Midwest in the early twentieth century. Centering a story in a midwestern town was not what sets Lewis apart from writers who came before him; it was the manner in which he portrayed those towns. Main Street was not simply Main Street in Gopher Prairie, but a representation of every American town. The sights, sounds, and people were all given names and identities, but none are exclusive to the plains of Minnesota. Main Street opens with this passage that shows exactly what Lewis was known for in his writing. It emphasizes the universality of his characters and settings:

This is America – a town of a few thousand, in a region of wheat and corn and dairies and little groves.

The town is, in our tale, called “Gopher Prairie, Minnesota.” But its Main Street is the continuation of Main Streets everywhere. The story would be the same in Ohio or Montana, in Kansas or Kentucky or Illinois, and not very differently would it be told Up York State or in the Carolina hills.

Main Street is the climax of civilization. That this Ford car might stand in front of the Bon Ton Store, Hannibal invaded Rome and Erasmus wrote in Oxford cloisters. What Ole Jenson the grocer says to Ezra Stowbody the banker is the new law for London, Prague, and the unprofitable isles of the sea; whatsoever Ezra does not know and sanction, that thing is heresy, worthless for knowing and wicked to consider.

Our railway station is the final aspiration of architecture. Sam Clark’s annual hardware turnover is the envy of the four counties which constitute God’s Country. In the sensitive art of the Rosebud Movie Palace there is a Message, and humor strictly moral.

Such is our comfortable tradition and sure faith. Would he not betray himself an alien cynic who should otherwise portray Main Street, or distress the citizens by speculating whether there may not be other faiths?

In

addition to describing his ability to relate the essence of small-town America,

this passage demonstrates another aspect that was inherent to the nature of

Lewis’s writing. Though Main Street is not a humorous book

by any standards, it is written with an entirely satirical edge. Gopher Prairie

is shown through the eyes of Will and Carol Kennicott. Will is a country doctor,

likely inspired by Lewis’s own father. He represents the common, hard-working

American, and sees his town as one. Recognizing the majesty in the pillars

of the bank building, the glory in the fall colors, and individuality of each

citizen of his small town, Will Kennicott does indeed see Gopher Prairie as

the “climax of civilization”. Carol Kennicott plays the devil’s

advocate, showing the reader the irony of Main Street. She recognizes,

as Lewis does, that there is nothing phenomenal about these few rows of houses

in particular, nothing extraordinary in this town over any of the others that

are sprinkled throughout the plains of Minnesota – or anywhere else

in the mid-west. It was this sense of irony, in combination with the ability

to portray the universal feature of small-town America that led Sinclair Lewis

to the winning of the Nobel Prize in Literature. He acheived this honor "for

his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with

wit and humour, new types of characters."

In

addition to describing his ability to relate the essence of small-town America,

this passage demonstrates another aspect that was inherent to the nature of

Lewis’s writing. Though Main Street is not a humorous book

by any standards, it is written with an entirely satirical edge. Gopher Prairie

is shown through the eyes of Will and Carol Kennicott. Will is a country doctor,

likely inspired by Lewis’s own father. He represents the common, hard-working

American, and sees his town as one. Recognizing the majesty in the pillars

of the bank building, the glory in the fall colors, and individuality of each

citizen of his small town, Will Kennicott does indeed see Gopher Prairie as

the “climax of civilization”. Carol Kennicott plays the devil’s

advocate, showing the reader the irony of Main Street. She recognizes,

as Lewis does, that there is nothing phenomenal about these few rows of houses

in particular, nothing extraordinary in this town over any of the others that

are sprinkled throughout the plains of Minnesota – or anywhere else

in the mid-west. It was this sense of irony, in combination with the ability

to portray the universal feature of small-town America that led Sinclair Lewis

to the winning of the Nobel Prize in Literature. He acheived this honor "for

his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with

wit and humour, new types of characters."

More Sinclair Lewis

Additional resources for Sinclair Lewis, including a complete list of works, his submitted autobiography, and the Nobel Prize in Literature presentation speech can be found here.