Copper Range Mining Company, White Pine Location (owned by Inmet Mining)

Copper Range Mining Company, White Pine Location (owned by Inmet Mining)

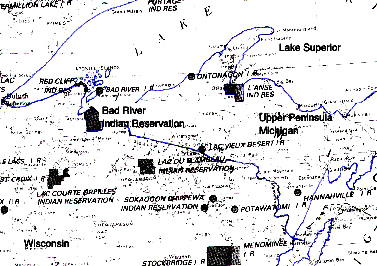

In addition, the tribe members fear potential acid pollution of the ground water due to acid seepage from the solution mining. The tribe members are concerned that the acid will contaminate the lands and waters upon which they, by treaty, have a right to hunt, fish and gather.

Sulfuric acid is, by far, the most widely used industrial chemical in the world. It is used in the production of fertilizers, chemicals, iron and steel, as well as in petroleum refining, electroplating, and nonferrous metallurgy. It is highly corrosive, dissolves most metals, and mixes easily with water. Sulfuric acid is a strong irritant to skin, and in concentrated form can cause chemical burns; in the air it can irritate the respiratory system and cause chest tightness, coughing, and may eventually lead to a buildup of fluids in the lungs. If discharged upon land it can kill vegetation, if discharged into waterways it can make them uninhabitable for most forms of wildlife.

However, there is some debate as to the danger of sulfuric acid. Sulfuric acid used at the mine is diluted at a 1 to 15 ratio from when it arrives, and is about as strong an acid as lemon juice. Earlier in the century sulfuric acid, in stronger solutions than those used at the mine, was often ingested as a common medicine. Additionally, the acid, when mixed with the high calcium chloride mine water, forms calcium sulfate (otherwise known as gypsum). The gypsum immediately precipitates out of the solution and forms an additional barrier to any release of the remaining acid. Therefore, the potential for seepage of acid from the mine is thought to be non-existent.

Unfortunately, however, there now exists great potential for acid seepage into the groundwater. Conventional shaft mining operations have breached an old sea bed at the site. Therefore, unless treated, salt water will eventually leach into the Montreal River and Lake Superior. As a requirement of the solution mining permit, the Michigan DEQ has required the mine to fund a water treatment facility to clean the groundwater, in perpetuity, after the mine is closed.

In 1995, the Copper Range Mining Company, after 40 years of operation, ceased conventional shaft mining (i.e., bringing copper bearing ore to the surface for further refining) at the Michigan, White Pine location, due to cost concerns. The company is currently testing the viability of utilizing the less expensive method of solution mining. Solution mining consists of rubblizing areas of the mine already developed by conventional shaft mining, and extracting the remaining copper by leaching it out of the rubble in a dilute solution (approximately 7%) of sulfuric acid; this process is confined within concrete walls. The copper laden solution is then pumped to the surface and the copper is plated out and the acid solution is reused.

In August 1994, US EPA stated that the project "does not involve what we determine to be any type of injection well and since MDNR (now MDEQ) has been extremely active in reviewing the project, we feel that there is no role for the (EPA well) program to play." After reviewing the permit application for 3 years, and working with US EPA, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) issued a permit to commence trial operation of the solution mining technique on May 28, 1995. At this time US EPA committed to reaching a formal regulatory determination regarding the commercial scale operation by no later than July 1997.

The initial testing is being conducted on about a quarter of a square mile and will produce about 1 million pounds of copper per year; if fully implemented the project will cover approximately 25 square miles, and could produce 60 million pounds of copper per year for 15 to 25 years.

Copper Range Mining Company, White Pine Location (owned by Inmet Mining)

Copper Range Mining Company, White Pine Location (owned by Inmet Mining)

Chippewa Tribes in Wisconsin & Michigan

Chippewa Tribes in Wisconsin & Michigan

Wisconsin Central Railroad, Rosemont, Il

Wisconsin Central Railroad, Rosemont, Il

National Environmental Justice Advisory Council

National Environmental Justice Advisory Council

US Department of Justice, Chicago, Il

US Department of Justice, Chicago, IlTo date, the tactics used by the members of the tribe include: a) formal requests for safety inspections of the railroad; b) a blockade of the railroad where it crosses the reservation; c) formal requests for federal review of the environmental impact of the acid shipments to the mine and the operation of the mine; d) attendance at federally sponsored public meetings; and e) civil protests at public functions.

July 2 - Trial operation of solution mining begins at the White Pine Mine.

July 22 - Approximately 12 Chippewa Indians blockade the railroad tracks where they cross the reservation. They seek inspection and repair of the tracks and bridges, an environmental impact statement for the mine, and development of a reclamation plan and an emergency response plan for the rail corridor. Although tribal officials support the blockade, it is not an official action of the tribe.

July 24 - Railroad officials delay shipments, meet with protesters, and review alternative means of shipping.

July 29 - Protesters seek copies of the bridge and rail inspection reports and the emergency response plan; they also hire their own rail inspector. The railroad agrees to develop a special emergency response plan for the reservation.

July 30 - Railroad officials ask the Sheriff to remove the protesters. He declines. Railroad officials say a settlement is unlikely.

August 1 - A mediator from the US Department of Justice is summoned to assist. Wisconsin Governor Thompson seeks assistance from US Attorney General Janet Reno and Interior Secretary Bruce Babbit to allow the trains to move. Some materials (not acid) are moved to the mine by truck.

August 2 - The railroad begins preparations to utilize an alternate andpreviously abandoned rail route. Officials from the Department of Justice meet with the Sheriff, the Tribal Chairman and officials from the US Bureau of Indian Affairs. US attorney General Doyle seeks a federal inspection of the tracks and an analysis of the environmental impact of solution mining.

August 5 - Questions surface as to whether the tribe is trying to test their power over reservation land; for although the Courts have stated that tribes have a fair amount of authority to regulate a variety of issues within reservation boundaries, federal laws regulating railroads may supersede the reservation sovereignty.

August 6 - The mine continues the trial operation of solution mining while the railroad continues working to open an alternate line to transport supplies and finished products.

August 7 - Federal authorities agree to conduct a full environmental analysis of the mining project and transportation safety.

August 10 - US Representative Stupak, of Menominee, Michigan, criticizes the blockade.

August 13 - Two trains are allowed to cross the blockade, an east bound and west bound, provided they carry no hazardous materials. The use of an alternate, previously abandoned, rail route is approved by the City of Ironwood for non-hazardous materials. The cargo will be trucked from the rail head to the mine.

August 14 - Wisconsin State Representative Linton, of Highland, announces proposed legislation to ban chemical mining in Wisconsin.

August 16 - The Ontonagon County Economic Development Corporation announces support for the mining project.

August 19 - The blockade is abandoned after 28 days, but tribal members say they continue to oppose the transport of hazardous waste across the reservation.

August 20 - Talks continue over rail traffic through the reservation. The railroad halts plans to utilize the alternate route.

August 23 - The mine produces its first copper via solution mining.

August 26 - The regular movement of trains along the rail line through the reservation recommences, however, no sulfuric acid is being shipped to the mine by rail.

September 4 - Walter Bressette of the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council announces a plan to demonstrate at the mine.

September 5 - It is announced that shipments of sulfuric acid to the mine had resumed, via truck, on September 3.

September 12 - The mining company rubblizes a second area of the mine to prepare it for the next phase of the solution mining pilot project.

September 18 - US EPA announces a series of public meetings to explain their position and solicit input for the scope of the environmental analysis. The meetings are to be held on September 23 through 26 with the Indian Tribes, the media and the community in Ashland, Wisconsin; with elected officials, the media and the community in Ironwood, Michigan, as well as with the community on the Keweenaw Bay Reservation. Ontonagon County officials, supportive of the mine, are "outraged" that none of the meetings are within the county.

September 23-26 - Public meetings are held. US EPA announces a fifth meeting will be held in Ontonagon County. US EPA also announces that it will not revisit the decision to allow the pilot project, calling the research done by the Michigan DEQ sound. US EPA also states that they believe that a formal Environmental Impact Statement is not required by law, however, they will conduct an Environmental Analysis, in the next 12 to 18 months, with virtually the same features. The analysis will be conducted based upon the federal governments "trust responsibilities" to Native Americans.

At the first public meeting, held on the Bad River Reservation, Odanah, Wisconsin, all verbal comments received were against the project, another 567 signed petitions, presented at the meeting, objecting to the project. At the third public meeting, held in Ironwood, the Ontonagon County Board of Commissioners reports over 1,000 signatures supporting the mining project.

October 2 - US EPA announces that the rail line through the reservation meets federal standards for the transportation of sulfuric acid. US EPA stated that they relied upon 4 track inspection reports, including one conducted by an independent consultant hired by the tribe.

October 4 - Railroad officials say that they will await tribal permission before resuming shipments of acid by rail. Chippewa tribesman Walter Bressette announces he feels "betrayed" by US EPA, and will conduct workshops on "how to take apart the rails." In addition, a protest group of approximately 35 people conduct a 2-hour demonstration near a function attended by Wisconsin Governor Thompson.

October 5 - The Wisconsin Central Railroad begins shipping sulfuric acid to the mine by rail, although the railroad is unsure if an agreement with the tribe is in effect.

October 12 - US EPA announces a public meeting will be held in White Pine on October 21.

October 14 - Copper Range announces that it will suspend operation of the pilot scale solution mining. The mining company noted that recent statements by US EPA that it would take 12 to 18 months and possibly longer to conduct the environmental analysis necessary to approve the full scale operation of the mine was the major reason for the suspension (previously, US EPA had committed to reaching a formal decision by July 1997). A mine official states that the company cannot continue to make expenditures in light of the uncertainty posed by the newly announced US EPA regulatory process. A Michigan DEQ spokesman states that US EPA has been "a full partner in writing every step of the permit" and that this action "takes federal bureaucracy to a full level of absurdity."

October 15 - A US EPA official states that his agency has worked with Michigan DEQ, but not on a step-by-step basis. He states, "we have great respect for what they have done, but we want to make sure it is complete."

October 18 - A US EPA official states, contrary to earlier analysis by his agency, that they have now made "a regulatory determination that this facility was regulated (as a well) under the (federal) Safe Drinking Water Act. I think we're confident that we have a valid interpretation of our regulations."

October 21 - The public meeting is finally held in Ontonagon County, at the city of White Pine. Michigan DEQ officials state that they stand behind the permit issued to the mine. State Congressmen Koivisto and Tesanovich, and representatives of US Senators Levin and Abraham and US Representative Stupak, reiterate their support for the mining project. These government officials along with many of the public questioned why, after declining numerous opportunities, did the US EPA wait until this point to decide it needed an Environmental Analysis. US EPA officials did not respond to this question, they also gave no estimate of how long the process of obtaining a permit, if one is determined necessary, would take.

These tactics led to recognition of the issue and federal intervention, which then resulted in an environmental review process which the mining company found too time consuming. The members of the tribe were successful in a number of areas, including having:

However, it is anticipated that the issue will not not be fully resolved in the immediate future. The mining company may pursue efforts to expedite the environmental review and recommence solution mining operations.

The author, however, strongly recommends a combination of local and area public protest and legal efforts in the federal courts. The local protests will place pressure from the bottom to the top of the bureaucratic heirarchy existing in Michigan and within the federal government. This pressure will serve to galvanize local support and gather media attention the of Chippewas' efforts, which will reverberate across the country as the struggle gains more momentum. That, combined with lawsuits under the Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Michigan Environmental Policy Act, and/or the Public Trust Doctrine, may put sufficient pressure on the state and federal government to provide more complete protection for Native American lands, specifically the Bad River Reservation.

US EPA, Chicago, Il

e-mail address: werbach.david@epamail.epa.gov

(312) 886-4242

Iron County Miner Newspaper

Hurley, Wisconsin

Lexis/Nexis Computer Information System

The Ethnic News Watch

The Ojibwe News