1931 Dracula

(Bela Lugosi)

(Bela Lugosi)

1931-1999 selections

|

Vampires

|

|

|

||||

|

1931 Dracula

(Bela Lugosi) |

1931-1999 selections

|

||||

| |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

audience of a horror film knows what it is getting. Indeed, it is likely

that the very nature of formula movies is at the root of their appeal.

It is comforting to feel such certainty in the world-particularly in the

face of the tribulations vicariously overcome in horror films. Outside

the darkened theater, there is little fear that the villain will be slain

and the heroes will survive. Beyond the reassurance of a victorious champion

of Good, what else is appealing about horror films? Perhaps the appeal

stems from how the story is told. An audience approaches a formulaic film

with a set of expectations established by the genre and measures the success

of the film by these standards. Did the director, actors, and technicians

bring anything new to the genre? Did they fulfill the expectations demanded

by connoisseurship? To entice audiences into trading their free time for

viewership, artists have been asked to design prominently displayed advertisements.

With the advent of television, the movie trailer has gained considerable

marketing power, yet posters are still produced and coveted by collectors.

Examining such posters may provide some insight into the perceived interests

of the target audiences.

The vampire figure has a long and storied existence. The earliest recorded use of the word in English occurred in 1734 (OED) and a keyword search of the Library of Congress reveals 240 volumes (discounting entries that refer to the species of bat) pertaining to vampires. Likewise, the Internet Movie Database (IMDB) provides 245 film titles with "vampire" in the moniker and over a hundred that contain the king, "Dracula." With such a capacious landscape, I will limit my discussion to the analysis of relationships portrayed in cinematic art: primarily movie posters. return to top  The

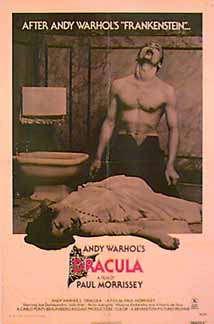

vampire is often depicted as a thwarted lover. A common image hitched

to the vampire and other monsters is the threshold carry. Like a groom

bearing his new bride through a portal, the character is depicted with

a woman draped over his arms. This scene is recognizable as a precursor

to the consummation of a marriage, a time of anxiousness and anticipation.

However, in the posters for the horror movies, the "bride" is limp and

often (at least) seemingly lifeless. The monster then becomes entangled

with Poe-etic tragedy: the loss of beauty (Poe, 1136). Death intervenes

with love. Notice the combination of images (the staking of the heart

and the flacid bride) depicted to the right. Death looms over the potential

of bliss. Like the poems "Annabel Lee" and "The Raven,"

the monster finds himself deprived of beauty, love, and understanding,

which ought to induce sympathy. The

vampire is often depicted as a thwarted lover. A common image hitched

to the vampire and other monsters is the threshold carry. Like a groom

bearing his new bride through a portal, the character is depicted with

a woman draped over his arms. This scene is recognizable as a precursor

to the consummation of a marriage, a time of anxiousness and anticipation.

However, in the posters for the horror movies, the "bride" is limp and

often (at least) seemingly lifeless. The monster then becomes entangled

with Poe-etic tragedy: the loss of beauty (Poe, 1136). Death intervenes

with love. Notice the combination of images (the staking of the heart

and the flacid bride) depicted to the right. Death looms over the potential

of bliss. Like the poems "Annabel Lee" and "The Raven,"

the monster finds himself deprived of beauty, love, and understanding,

which ought to induce sympathy.  However,

the above poster complicates our reaction by disturbingly depicting the

vampire as the embodiment of the taboo of necrophilia. The woman, now

deceased, is still bourn as a bride on her way to her wedding bed. This

hint at forbidden conduct adds macabre titillation to the horror of the

walking undead. Regardless of the resulting ethos, the vampire is a melancholy

entity denied love in penance for his worldly or other-worldly sins.

return to top However,

the above poster complicates our reaction by disturbingly depicting the

vampire as the embodiment of the taboo of necrophilia. The woman, now

deceased, is still bourn as a bride on her way to her wedding bed. This

hint at forbidden conduct adds macabre titillation to the horror of the

walking undead. Regardless of the resulting ethos, the vampire is a melancholy

entity denied love in penance for his worldly or other-worldly sins.

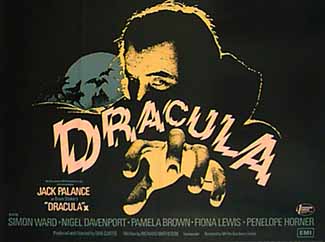

return to top The destructive fiend, however, is another way that vampires have been marketed. A predator is frightening only when it has the power to obtain its prey. As mankind has used his ingenuity to tame the dangers of the wild, he has become comfortable on a regular basis. Perhaps harbored somewhere in the subconscious is the suspicion that our dominance is temporary. Perhaps a mightier king may come to claim our hill. Enter the vampire. Vampires are often imbued with excessive strength, unworldly quickness, and the ability to change shape. Defeating the undead often requires a learned expert, armed with tradition and tactical weapons (crosses, holy water, garlic, etc.) that attack the unholiness of the creature (Wolf 29). Without attending to tradition and homely wisdom, one may fall prey to the dangers that lurk in the night. Note the unearthly tint to the vampire, concealed mostly in darkness. The hand is reaching, not for some peer upon the stage but for you the audience member. Dracula is not just a threat to Mina, Lucy, or Harker, but to us as well.  Our

fears of inferiority and vulnerablility are to be tested by the film.

Therefore, posters such as this challenge the audience to safely face

their inadequacies, knowing that the formula will save them by the time

the last reel has cleared the projector. This could be said of virtually

any malicious monster, however. Our

fears of inferiority and vulnerablility are to be tested by the film.

Therefore, posters such as this challenge the audience to safely face

their inadequacies, knowing that the formula will save them by the time

the last reel has cleared the projector. This could be said of virtually

any malicious monster, however.  The

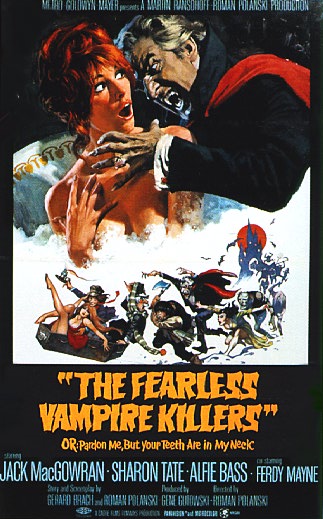

vampire is a particular case because he or she is often a sexual predator.

As seen in the advertisement for The Fearless Vampire Killers-US

edition, the vampire is a fiend attacking a woman. Note the red hair of

the victim, often a sign of a "wild woman" in movie lingo, and her manner

of dress (or lack thereof!). Although she is resisting, it is suggested

by her appearance that she is not adverse to physical encounters. Her

resistance seems to be of no avail against her antagonist-the flowing-haired,

bared-fang vampire who has a firm clutch on his prey. He is not portrayed

sympathetically. It appears that a woman misguidedly made herself available

to the wrong suitor and is about to pay with her life. Therefore, not

only does the vampire serve as a humbling device, he becomes the instrument

of punishment for violating the taboo of blatant sexuality.

return to top The

vampire is a particular case because he or she is often a sexual predator.

As seen in the advertisement for The Fearless Vampire Killers-US

edition, the vampire is a fiend attacking a woman. Note the red hair of

the victim, often a sign of a "wild woman" in movie lingo, and her manner

of dress (or lack thereof!). Although she is resisting, it is suggested

by her appearance that she is not adverse to physical encounters. Her

resistance seems to be of no avail against her antagonist-the flowing-haired,

bared-fang vampire who has a firm clutch on his prey. He is not portrayed

sympathetically. It appears that a woman misguidedly made herself available

to the wrong suitor and is about to pay with her life. Therefore, not

only does the vampire serve as a humbling device, he becomes the instrument

of punishment for violating the taboo of blatant sexuality.

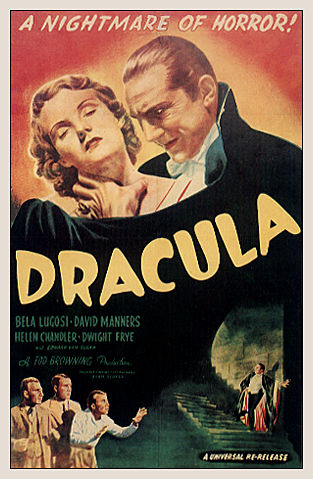

return to top Finally, the vampire is at times depicted as the seductive stranger. The attractive vampire has been seen as a picture of elegance: a gentleman like John Polidori's Lord Ruthven (Wolf, 98), or a lady such as Sheridan Le Fanu's Carmilla (Auerbach, 38). The shroud of mystery distinguishes the exotic vampire from the plentiful mediocrity of the population around us. The familiar flaws evident in fellows the audience knows well are not revealed by the outsider who keeps to himself. With curiosity, the quarry offers herself willingly to the suave hunter. "Most important was the sexual attraction of Dracula towards his victims, which is the fundamental power of evil," declared Terence Fisher, the director of many of Hammer's films (Brosnan, 113). A need is perceived and an exchange is offered. The sense of sacrifice or the exhilaration of flirting with the edge of catastrophe draws the protagonist close the vampire. The neck, home of the vulnerable jugular favored by vampires, is bare in both posters below.  In

the Vampire in Brooklyn advertisement, the woman's eyes are closed

and her head is tilted back-awaiting a bite or a kiss-demonstrating trust.

The vampire's hand is held near the neck and in reserve. Contrast this

with the image from the 1931 Dracula In

the Vampire in Brooklyn advertisement, the woman's eyes are closed

and her head is tilted back-awaiting a bite or a kiss-demonstrating trust.

The vampire's hand is held near the neck and in reserve. Contrast this

with the image from the 1931 Dracula  where

the hand is firmly clutching the prey, inhibiting escape. The 1995 film

depicts a vampire with self control, therefore reinforcing the sense of

safety and prolonging the anticipation of action. The other seductive

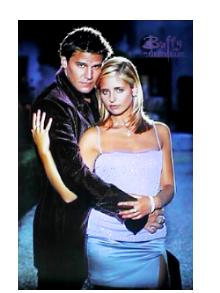

stranger image represents television's version of Buffy the Vampire

Slayer. Again we have the male/female arrangement, but notice the

orientation. Both characters face the viewer, pressed closely together.

The hand we see in this poster belongs to the woman, not the vampire.

She is entwined with the creature of the night, where

the hand is firmly clutching the prey, inhibiting escape. The 1995 film

depicts a vampire with self control, therefore reinforcing the sense of

safety and prolonging the anticipation of action. The other seductive

stranger image represents television's version of Buffy the Vampire

Slayer. Again we have the male/female arrangement, but notice the

orientation. Both characters face the viewer, pressed closely together.

The hand we see in this poster belongs to the woman, not the vampire.

She is entwined with the creature of the night, a gesture of intimacy, while her back is turned to him, a sign of trust.

The dark clothing and downward tilt of the head are classic trademarks

of the brooding outsider. The mystery attained from being an outsider

permits the viewer the opportunity to project desirable qualities into

those shadows. Therefore, these posters use the seductive stranger to

entice viewers into a vicarious flirtation or affair. return

to top

a gesture of intimacy, while her back is turned to him, a sign of trust.

The dark clothing and downward tilt of the head are classic trademarks

of the brooding outsider. The mystery attained from being an outsider

permits the viewer the opportunity to project desirable qualities into

those shadows. Therefore, these posters use the seductive stranger to

entice viewers into a vicarious flirtation or affair. return

to top In conclusion, artists use different facets of the vampire image to whet the appetite of the movie-going public. With such a rich tradition in literature and film, the vampire has a dynamic and multi-dimensional personality. At times, the vampire is the sympathetic figure of tragedy, the ruthless scourge of loose morals, or the greener grass on the other side of the fence. The hopes and fears of the potential audience provide opportunities for artists to explore and reinvent the vampire to meet the needs of a huge array of events in film. return to top |