Dorothy Lewis Patterson

Dorothy graduated in 1958 with a Bachelor of Science in Aeronautical Engineering. She worked as an aerothermodynamics engineer at Chrysler Missile, as an aerodynamics engineer at General Dynamics, and as an engineering librarian at General Dynamics/Hughes. She has three children.

Growing Up

Listen to Dorothy describe her family and discuss why she transferred from LS&A to the School of Engineering.

DP: Well, there was my mother and father. My father was a lithographer and mother later on took classes and became an accountant, but during the time that we were at home she was a housewife and my sister Pat, who you have interviewed, and me. That was it. And Pat is more than six years older than I am and she was eight years ahead of me in school because they let her start early and I had to wait. So, we really grew up like two only children.

KW: Oh really? Did she have any influence on your decision to...because you both did aeronautical engineering, correct? Did she have any influence on that?

DP: I suppose in a way. When I started college I was a chemistry major. I really liked chemistry. I was in lit. school and thought this is just a terrific thing to do. And I didn’t think about going into aeronautical engineering and I probably avoided it in fact because Pat had already done that. But it became apparent to me about the third semester in chemistry that this was really not where I was happy. I was in lit. school. I guess you still call it lit. school...

KW: Yeah, the liberal arts school?

DP: Yeah literature, science, and the arts. We always called it lit. school and chemistry majors were in lit. school. And I found that in my classes I did not feel like I was at home. I felt like "These are my classmates?” (laughs) “Weird!” I got tired of listening to people pontificate in English class and you know. I just didn’t feel like I was in the right thing. I thought about various things and my second semester my sophomore year I just kind of marked time I guess. I took some courses that were interesting to me, one of which was organic chemistry (laughs). I really enjoyed that one but I had a lab that washed me out of chemistry. But anyway, somewhere along the line, I had taken an art history course trying to fulfill my soc. requirements, which were the hard thing for me. And that course really had a great influence on my future career because while I enjoyed the art part of it what I really liked was when they got into the architecture and such, showing the Greek construction and how it failed and then showing the Roman arch that would allow greater expanse in a building and then the arches which allowed even more and these great cathedrals that you could build. And I was just absolutely fascinated with the idea of the stresses and strains and how these cathedrals, everything on them is necessary to keep the thing standing. It’s just amazing. I got really interested in that and I thought, “You know, I really am more technically inclined than anything else." So, muddling around, I did go over and take a test to see what I really was suited for and I remember taking it, that I went through it, I had no trouble making any decisions on the answers. I just whipped through it and I looked around and everybody else was sitting there with their head in their hands over this thing and I thought “Oh, I must have screwed up somewhere." So, I went back over it again and I thought, “No, there’s nothing I’m going to change", so I finally just stood up, walked up, and handed it to the teacher or mentor or whatever and walked out. And when I got the results it said mechanical engineer with a question mark since I was female and the guy that talked to me said that the man in there watching us take the test said, "Even the way she took the test, she belongs in engineering,” (laughs) just became I wasn‘t having any trouble making decisions. I could answer the questions. So, anyway, I decided what the heck I might as well go into aeronautical engineering. I always liked airplanes too. When I got into those classes I felt much more at home. My fellow students, while obviously very different from me because they were all male, nevertheless were more like me in personality.

Listen to Dorothy talk about how she loved reading non-fiction books as a child even though there weren’t many as a result of World War II paper rationing.

DP: Oh yes. I was interested in science before I even knew what it was, I guess. I had a set of encyclopedias that were child-friendly that were fun. I would just take one of them and just read the parts I was interested in, which was always animal life or various other sciences and that sort of thing. Then when I got into grade school one teacher would always go over to the high school library and get books and bring them back. That had all the school’s libraries over there in one place and she would bring back books that we could read in our free time when we’d gotten our schoolwork finished. And I remember one time she got one called "A Junior Science Reader" and it had an explanation of the solar system and all these things and I kept begging her to get more books like that and they just weren’t available. So, when I did get into that library job later I would look at the books that were available for children now and they weren’t available when I was a child, and part of this was the fact that I was a child during the second World War and they weren’t printing books very much or there were a few of them but it was a very different world than anything you’ve ever experienced because it was...everything went to the war effort and all manufacturing, food, everything else, the armed forces got it first and what was left we got and things were rationed. There were some books printed on very poor paper that probably don’t even exist anymore because they just kind of crumbled. So, living in a small town, I was born and raised in Sturgis, Michigan incidentally and I don’t know if you know where that is but it’s in a farming area, it was a town between, I think, seven and eight thousand back then and I don't think it is any bigger now. It was a very, well, it's difficult to put this but it was largely a white town. Not because of any restrictions just simply the other races weren’t attracted there. At the time there were two black families in town and they were both a little ahead of me in school but I knew the boys because they played sports. But there weren’t a lot of things...I did go to the public library, we had a Carnegie branch, and I read an awful lot of books from there. In fact, I was interested in drawing and I think I read every Will James book that was ever written and after I would get through reading it then I’d go through and copy all the horse pictures. So, I had a lot of different interests as a kid. But remembering my childhood, I spent a lot of time climbing trees and riding my bike and I loved playing in the snow, building snow forts and snowmen and I had a dog that was my best buddy. I was always able to amuse myself. I didn’t have always have someone around, although I did have very close friends up through junior high and then I got in with a couple of other friends for my high school years.

KW: Well, it sounds like growing up you sort of knew what you wanted or what you were interested in and then you went after it. It definitely sounds that way with the books.

DP: Yeah. I always liked reading and I liked learning, that was the whole thing. I didn’t read fiction even as a child. I mean I did read some but I remember not reading the Little House on the Prairie set. You know, all the girls in class kept telling me, “Oh ,you really ought to read this book.” I said, "I don’t want to read about a little girl.” I liked Winnie the Pooh; I liked animal stories, Aesop’s fables. I guess I really didn’t like people all that much that I wanted to read about them (laughs). It's a terrible thing to admit, but I was just interested in nonfiction. I really wanted to learn even as a child. I always set goals and I don’t remember ever being any different.

University of Michigan

Listen to Dorothy describe the differences between her peers in LS&A and those in the School of Engineering.

DP: Engineers tend to be rather retiring, reticent, shy (laughs). That’s me. And I don’t know, it was just something about it. They’re down to earth; they have a wonderful sense of humor, but you have to get to know them. You have to talk and kind of feel people out and, you know, you get to know each other slowly and you don’t hear any of them holding forth and trying to impress one another. And I got so much of that in lit. school I just thought, "Oh my God, I can’t handle it. I do not belong here". So, anyway, I was much happier. I won’t say engineering was easy; it certainly wasn’t, but it was the right thing for me. I could have gotten through school more easily I’m sure. I have a lot of other interests that I’ve gone on in later life to develop and I probably...if I had taken some anthropology courses, which I always wanted to do while I was there. If I’d taken them I might have majored in that, who knows? But engineering I really felt like that was the place for me and I enjoyed it and I’m glad I did it. I’m glad I stuck it out.

KW: Right.

Listen to Dorothy discuss her decision to attend U of M, which her sister, Patricia Pilchard, helped make easier by graduating from the School of Engineering several years earlier.

DP: Oh yeah. No, we were raised that the natural transition from high school was to college. My mother made sure of that. She did not...neither she nor my father actually ever got their high school degrees and mother was a self-educated woman too. She read a lot, there were always books in the house; she was always reading and she liked to learn and she set a very good example for both Pat and me. So, I never had any doubt. And Pat went to the University of Michigan and I just assumed I would go there too. Partly as a natural resource, but you know once you get away from the place and get out in the rest of the world and find out how highly regarded it is, it’s pretty nice. But Pat went there and I remember going up to football games and driving to Ann Arbor to take her back to school and everything and just always figuring, “Yeah that’s where I would go".

KW: So, friends, family, everyone just kind of assumed...there was no surprise about you going to University of Michigan?

DP: No.

KW: What about when you decided to switch from chemistry to engineering? How did your friends and family react to that?

DP: I don't remember anybody saying anything about it (laughs).

KW: I think your sister mentioned that initially your father was a little bit reluctant about her doing engineering.

DP: Yes.

KW: Did that kind of fade by the time that you were in school?

DP: Yes, definitely because Pat had gone and she had done very well and they were used to girls doing different things by that point. My sister was much more of a rebel than I was. I mean she was the one who would do something and ask forgiveness later and I was always the timid one: “Can I do this?" “No!” (laughs). She was much more adventuresome than I. And I didn't want to look like I was following her, so I had kind of avoided aeronautical engineering I suppose for that, although I hadn’t really considered it before I finally realized I was in the wrong field once I’d been there for a couple of years. And I did have the luxury of being able to change, which I’m not sure happens anymore. I think people sometimes have to commit themselves to whatever they want to study before they even enter college.

KW: Yeah, it’s difficult to even finish in four years now.

DP: Well, I took five and a half because of switching majors. I had sixty hours of non-technical electives when I went into engineering school (laughs). Hardly needed anything. I did have to take one further English course there but after that it was all engineering.

KW: Well, in retrospect it was probably worth it, that extra year and a half.

DP: Oh yeah it was. There were a lot of different courses that I can see later on that helped me grow and make the right decisions in a couple of situations. It was all a good experience.

Listen to Dorothy talk about living in Stockwell, a League House, and an apartment.

DP: Stockwell Hall.

KW: They’re actually renovating that right now. They’re making it a little bit bigger.

DP: Are they? I just loved that place (laughs). I never wanted to be in a sorority and my roommate and I were there together for four years and then they threw me out and I lived in a League House. I don’t even know if it exists anymore. Is Ulrich’s still there? I'm losing which one is South U and East U...it was over beyond the architecture school even. It was on Hill Street, that was it. No, it wasn’t Hill. Anyway I can’t remember.

KW: What do you mean by League House?

DP: It was for graduate students and there was a woman who rented out the rooms to us. It was under University supervision. But you had to arrange for your own meals; it was just a place to sleep and study and all that sort of thing. There was another girl and I who shared a room, we knew each other from Stockwell and we both weren’t going to be graduating in four years, couldn’t live in undergraduate housing anymore, and it was mainly for graduate students. But people in a situation like I was in could also do it. Let’s see, I was there...I should have graduated in ‘56 so I was there in the fall of ‘56 and then in February of ‘57 my husband and I married and then we had an apartment. That was about two miles from campus.

Stockwell Hall, ca. 1940-19501

Listen to Dorothy describe campus life including her favorite activities.

DP: I didn’t have time to be real close friends with anybody. My roommate and I stayed together all those four years and kept in touch.

KW: Was she an engineer? What was she studying?

DP: No, she was not. She ended up in dental hygiene. She started out as a teacher and she wound up in dental hygiene. And we were good friends, we got along real well. But you know I was not one who was sociable. I can remember just going for dinner. I worked in the dining room, so I would hear these girls talking about “Oh, H.O.B., H.O.B.," which was “hand of bridge". You know, “When we get up to our rooms we’ll play a hand of bridge.” Well, that would go on for all hours and some of them weren’t there the next semester and more of them weren’t there the following year whereas I would go up, grab my books, and start studying. If I couldn’t study in the room, I would go down to the study hall. And after my roommates would go to bed I would be down in the basement of Stockwell Hall cramming away (laughs), trying to get my homework done because I had a lot of it. And I was very determined to always get my stuff done. I put my schoolwork first, that was the main thing I was trying to accomplish. And I always had more homework than I knew what to do with.

KW: So, it was kind of hard already to balance friends with schoolwork.

DP: Yeah, it was. And it’s not that I didn’t have good friends. I certainly did, although most of us haven’t kept in touch after we got out of school. But we occasionally would do something like go to a movie or something like that but mostly...I met Bob fairly early on in college and so spare time I was spending with him and we’d go to the Arb or something like because we never had much money to go do anything exciting. Went to fraternity parties; he was in a fraternity.

KW: Were you involved in any clubs or organizations on campus?

DP: No.

KW: Was there much of a variety of things to do at the time or how would you describe it?

DP: Well, there were always football games of course, that was a big thing, and we used to go to the hockey games, loved that. But you know, mostly things like that or going to fraternity parties. Occasionally went to a movie or something of that sort. But as far as, you know, clubs for women in engineering, no, there was nothing. There were no organizations or support groups or anything of the sort. I had orientation when I went in as a freshman in lit. school, but when I went to engineering school I was strictly on my own. I got to know guys in my class of course.

KW: Did you feel like an organization was necessary because you seemed very driven and focused already on your own?

DP: No. It’s kind of funny because I remember getting a questionnaire once before wondering how important the support groups were and my answer was “What support groups?" (laughs). There weren’t any. But no, I didn’t really need them. Some of the guys in my class and I used to talk on the phone over homework or something like that but once they knew I was not a threat, that I wasn’t in there looking for a man or anything like that, they were all very friendly to me and I had a good time with them.

Listen to Dorothy discuss the impact the returning Korean War veterans had on her classes at U of M.

DP: Well, the Korean War...well, both I guess. The Korean War was going on when I was in high school and first in college. What happened there was that we had returning veterans from the Korean War who came and wanted to get a degree in aeronautical engineering. They already had, they were pilots, they already had a degree from probably West Point and so they were looking for a master’s. But in order to get the master’s in aeronautical engineering, they had to take all undergrad aero courses because they hadn’t had anything like that before. So, this made the competition pretty stiff. But they were fascinating guys. One of them had been a prisoner of war and had been written up in LIFE magazine and all sorts of things and he was a real nice guy, I liked him. But he and his wife had apparently broken up because of what he’d gone through. They never showed any strange behavior or antisocial or anything else; they were just fascinating guys, showing their flying missions with their hands and all that sort of thing.

KW: Well, yeah, they had experienced a lot.

DP: Yeah, they had and so they added a lot of interest to the course.

KW: When you say competition though, I’m assuming it was relatively friendly competition?

DP: Well, it was the fact that they had to maintain a "B" average, so you’re competing academically against these guys that have got more experience. And I found that when I went back and took a course or two in college that just being out in the world for a little while gives you a tremendous advantage (laughs).

KW I bet.

Listen to Dorothy describe her interactions with her male classmates and professors including their reaction to Sputnik the day after it launched.

DP: I think, aside from one huge lecture hall with one other woman in there, I was always the only one. It didn’t bother me.

KW: It wasn’t intimidating at all? Did your male classmates just treat you as one of the guys? What was the relationship like?

DP: Well, like I said, once they knew I wasn’t in there trying to charm them, that I was in for trying to get an education, I never had any problem with them. I never had any problem with the professors. I take that back. There was one math professor that I think did not like women and he made my life a living hell until I finally just dropped the class because I thought “this is ridiculous”. I was having trouble, in the first place, in this math class and I don’t know whether it was his inability to explain it or what but he would frequently call on me and I wouldn’t he able to answer and it just got to the point where I was so intimidated I didn’t even want to go in class. I thought, "I’m going to have a nervous breakdown." So, I finally said, "You know I really need to get out of this class and try again," and I did. I took the same course the next semester and did fine in it. I didn't have what it takes to prove myself and say, “By God, you’re not going to intimidate me.” (laughs) I was too much of a wimp and so I let him. But one thing that I should tell you, talking about war experiences, during October of ‘57 I woke up one morning and heard this strange thing on the clock radio, this “beep beep beep” and then the announcer came on and said, “That’s the sound of this Russian satellite," and, you know, “Oh my God!". So, I went to class, it was my final semester, it was a senior design class, and we had this professor that was just a real kick. He had come out of industry in California to teach propulsion courses. They had replaced the one semester of propeller theory with two semesters of propulsion theory classes and he was teaching it and then he was also teaching the senior design class where we had to design a little private plane. So, all of us were sitting around in class talking about this thing and what it meant and some of the guys think well maybe they’ll, instead of trying to get a job right now because the interviews hadn’t been all that many or positive about the chances of getting jobs in the fall, and so they were talking about, they thought maybe they would stay on and get a master’s degree and then be better qualified to go out and work against this, you know, help the U.S. efforts to put something in orbit. And our professor walked in. He didn’t say hello or anything else; he just walked across the room like he always does and said, “Well, I’ve been working on this,” (laughs) “and by the cold grey light of dawn I’ve figured out what, by backtracking, what kind of thrust it required to get this thing into orbit." So, he started writing on the blackboard on the left side and he just covered the whole thing, just talking a mile a minute, figuring out how much thrust it had taken to get that satellite into orbit and I don’t remember the figure anymore but it was a pretty astounding number to us. Much higher than anything we had been working with or thinking about. Of course the planes we were designing were propeller driven in spite of having the jet classes and all that sort of thing (laughs).

KW: I just wanted to ask, during the Cold War were you personally...were you truly fearful of the Communist threat? Of the Soviet Union? In retrospect it’s easy to say, “Well, nothing really happened," but at the time, what was it like for you?

DP: Well, the threat was always there and you felt it keenly that they got something in space before we did and it was, I didn’t actually work very much in industry towards that sort of thing but yeah, it was kind of intimidating. But I’ve always been a very optimistic and the sort of person when I figure, “There’s not a damn thing I can do about it anyway. I might as well have at good day while I'm at it.” (laughs)

Listen to Dorothy talk about her favorite professors and how they helped her.

DP: Yeah. I had one professor that...I can‘t even remember which course it was, I think it was engineering mechanics...that, I had had a little trouble with that, and he showed me the way and all that sort of thing. He was very friendly and nice and he even wrote me a letter during the summer encouraging me to continue on with my education, not that I had any doubt that I was going to drop out or anything like that. And I had some real good aero profs. Harm Buning who just died recently, I guess about a year ago in May. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of him.

KW: No, I haven’t.

DP: Probably, if you’re not in engineering school. He was a graduate student when Pat was there. He was born in Holland and he never lost his Dutch accent but he was so much fun and such a good prof. And we had some very good professors in the school. I don’t recall...I never felt I was treated any differently than the guys in class. Didn’t seem to bother anybody except that one guy and I brushed him off. I had another interesting one too. It was a course that all engineers were required to take and it was Chem. Met. 5, it was Strength of Materials and one of those great wash-out courses. I did very well in the class and he took me aside right before the final and said, “You know if you take the final, the only thing you’re going to do is possibly ruin your grade, so you don’t have to take it.” And then later he said, “Well, you’ll have to come in at least," and so I sat there wondering if I should have been studying for the darn thing. He motioned me and wrote something on the paper, you know I had to sign my name on it or something, and he said, "Okay, have a good summer." (laughs) Gave me an “A” in the class. And I hope it wasn’t because I was a girl. I mean I felt like I honestly earned it because I did get good grades on the tests and all that sort of thing. But my husband has never let me forget it because he was in Chem. Met. and he didn’t get an “A” in the course (laughs).

Listen to Dorothy discuss her favorite classes.

DP: Just in my life, to straighten out my thinking a little bit and that sort of thing.

KW: Were there any in particular that you remember as really enjoying or really disliking?

DP: Well, some of the English classes that I had in lit. school I found to be rather annoying (laughs). I think those were the ones that I had the most negative...just because, I don’t know, there was just something about the attitude of everybody in there that...

KW: Yeah, a different kind of person.

DP: Yeah, just didn’t jive with me. I enjoyed my German language classes that I took. Trying to think what else...the chemistry classes were interesting. I got used to an east coast accent (laughs). Couldn’t understand what the “lors” were that he was talking about until I finally figured out it was "law" (laughs).

Career and Family Life

Listen to Dorothy describe her first job after graduation at Chrysler Missile.

DP: Chrysler Missile in Warren, Michigan (laughs). I had to stay in Michigan. I had an offer from Douglas Aircraft on the west coast but because Bob hadn’t finished his degree, we had to stick around, so I took this job at Chrysler Missile and they were building Redstone and Jupiter missiles and they were in cooperation with the Redstone Arsenal in Alabama where Wernher von Braun was, you know, the German scientist who had developed the V-1 and V-2 missiles in World War II. And so these were kind of offshoots of those missiles and it was mainly a manufacturing plant but the engineering desks were scattered around in there too and I worked there for awhile until suddenly I was pregnant and had to give up my career for a twenty year maternity leave, as my husband always refers to it.

KW: Oh okay.

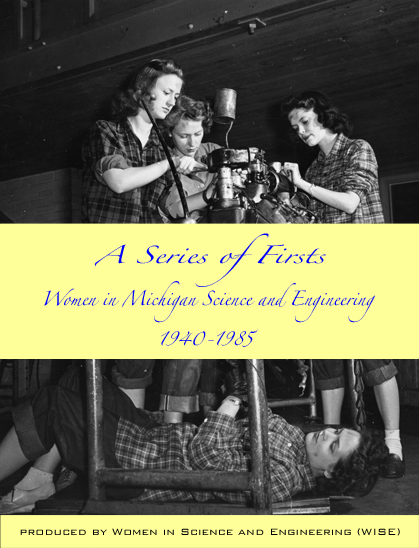

Dorothy Patterson, 19562

Listen to Dorothy tell her story of how she met her husband on a blind date.

DP: No, it was a blind date, believe it or not.

KW: That’s funny. How did that happen?

DP: I was up late one night in the restroom and one of the girls came in and she was looking for two girls to date a couple of guys in this fraternity that her boyfriend was in and I was too tired to argue and “Oh what the heck, you know, I need a night out,” and somehow my husband, as a fraternity big brother, found out something about the other girl. I was supposed to go with the older and shorter of the two fraternity brothers. He found out something about the other girl, so he switched the names, so I wasn’t even supposed to he going with Bob but, you know, it turned out we liked each other and we’ve been married now for fifty years.

KW: Oh wow. Well, congratulations, that’s a great story to tell.

DP: Yeah, it's pretty funny but that’s how it happened.

Listen to Dorothy talk about the work environment at Chrysler Missile including how every woman, even engineers, had to take a typing test.

DP: Well, mainly the fact that it was in Michigan and I had only gotten two offers. It was a slow time for engineers right then. And I could work there and Bob could continue his education.

KW: So, he was still in school?

DP: He was still in school, yeah. It was a fun job. You started out on kind of a training program where you went from one section to another and most of them were positive experiences. I had one where there was one guy I was working with who was a bit of a jerk and unfortunately I had to work under him until finally the supervisor took me aside one day and wondered what the heck was going on (laughs) and I said, “Well, we have a personality conflict,” and he says, “Oh, I wish I’d known," and so he switched me over to somebody else and I was fine. I don’t know whether...I really don’t know what it was, there was just kind an inherent dislike between us, I guess.

KW: Yeah, just a clashing. How many years were you there?

DP: It was actually a matter of months. I started...well I graduated in ‘58 and I started there right afterwards and then...I guess actually it was a little over a year...I had to quit in June of '59 because our daughter was a couple months away from being born so it was about eight months that I worked there.

KW: So, overall, it was a pretty positive working environment?

DP: Yeah. The one thing I hated was the fact that it was an old factory and we’d leave our little cluster of engineering desks and we would have walk up a flight of stairs to get to the women’s restroom and this meant walking through the assembly line. And there were always these jerks out there with their cat-calls.

KW: Oh, like construction workers nowadays.

DP: Yeah and it’s just “Oh god” and I wanted to go over there and say, “Would you treat your wife or your daughter this way or would you like to see your wife or your daughter treated this way?" I never did but it used to really annoy me. And of course those were the days when you wore hose and high heels to work and all this stuff which doesn’t make it any easier, walking along in high heels. It still makes me mad to think about it.

KW: How many other women were working there? Were there other women engineers?

DP: I don’t think so. There were other women but they were secretaries and some of the women would plot graphs and things like that, the kind of thing I did during the summer in high school. I spent a summer in Columbus, Ohio and a summer out in California working with engineering data, stuff that’s done automatically by computer now. It was all done by hand before.

KW: We actually sent out a survey to you a few years ago and I was looking at it before I called you and I noticed that you mentioned that all women had to take a typing class? Is that true? Regardless of the position they were applying for?

DP: Yeah, you always had to take a typing test and I was a lousy typist. I mean why did I go into engineering? I couldn't type! (laughs) You know, women were discriminated against, still are to some extent, but it's nothing like it used to be.

Listen to Dorothy discuss the impact her education had on her motherhood.

DP: Yeah, we joked about it. It was a twenty year maternity leave. I really enjoyed staying home with the kids. I didn’t have any ambition to go back. I felt like, "If you’re going to have these kids, you might as well raise them.” I never regretted it. It was fun. There were times I could explain things to them that other mothers probably couldn’t. (laughs) I definitely raised them to understand that women were every bit as intelligent as men and entitled to the same rights and all that sort of thing. I have this running thing with my number two son, but it's just always good fun, you know? (laughs) But in fact he’s been for women candidates a couple of different times when they were running. Elizabeth Dole I remember him admiring. I definitely raised them to be open-minded and accepting of women in any role. I think it helped.

KW: So, you were happy, you found fulfillment raising a family and you didn’t have any regrets...

DP: Yeah, I did. And also that little job I told you about, you know, because I always took time to read. I read to them too and got them interested in books. My daughter is a book-a-holic. The boys don’t seem to find as much time to read but they do occasionally.

Listen to Dorothy describe how she became the Engineering Librarian for General Dynamics despite having to adjust to using personal computers.

DP: Yeah, well, what happened was with our daughter in college and our two sons approaching it, it became obvious I was going to have to go to work to be able to afford to put them through college because we raised them the same way: “You will go to college." Or, I mean, it wasn’t that, it was that that is the natural progression, from high school to college. So, I went to work for General Dynamics and I went into the aerothermodynamics department, which was the part I had liked best. I think one of my favorite engineering classes was thermodynamics and I liked aerodynamic heating and that sort of thing. So, I got into the department and it was terrific, but I had left engineering twenty years before using a slide rule and a calculator and I came back and they were using computers.

KW: What was that like?

DP: That was, well, you know I had had a little bit of introduction to computers before I left college, but they were analog computers, very different from what they were using when I got into work. I figured, “Well, okay, this is how it is". I learned how to do it, although my typing skills betrayed me because it was during the age when the IBM cards you had to type out and usually the last stroke I’d make would be wrong and I’d ruin the whole card and have to start over again. But I worked with an aerodynamicist that showed me how to use this computer program to take wind tunnel data and reduce it to the form that they needed it for computing the different aerodynamic forces on missiles. General Dynamics was working on standard missiles for the Navy and that was what I worked on quite a bit. They also had another program, the Stinger missile, which you probably have heard of, which is an Army weapon. The Navy owned this building so they didn’t like anybody working on an Army project in their building so they split off and had an Army division set up and about that time we did not get the contract that we were sure we were going to get that I had worked on. So, they had to cutback the aerodynamicists or cut back engineers all through the plant and there were something like fourteen aerodynamicists and in a missile factory you really don’t need that many aerodynamicists because it’s a pretty simple thing, aerodynamically, compared to a plane. So, anyway, definitely since I was about the last one hired, I would be first out the door. At about that time in the new division that the Army had set up, the librarian over there quit in a huff and my boss found out about it and he said, "I’m going to go talk to the librarian here and see if maybe you can get that job,” and so he did and they talked to me and it was kind of a deal where I would go do that job until they got somebody with an M.L.S. while I tried to get back to my engineering job. And a few days after I’d been over there working, the head librarian came out and said, “Hey this job is yours as long as you want it.” Well, I like organizing things and they had a bunch of stuff that needed organizing and cataloging and I’d worked at a library long enough that I knew how to do that and I could do the computer by this point and I could do searches for people and find literature for them and I could handle all this stuff. So, that’s what I wound up doing for the last several years of my career. The main part of it, actually, I worked about three years as an engineer and about twelve then as an engineering librarian. And, you know, aerospace has its ups and downs and in another down they decided that they would lay off a lot of people and they laid off everybody in the libraries except I was the head in one division and my boss was the head in the other one and then one day she called me and said she’d been laid off, so I thought, "Oh boy here it comes," and they came and said, “Well, you’re now the head librarian and we’re going to move you back to Pomona when they combine the divisions again." Then they closed the Convair Library down in San Diego and I was the last GD librarian on the west coast (laughs).

KW: Wow, you really held out there.

DP: Well, it was kind of funny because here my boss would always refer to me as a non-degreed librarian because I did not have a Master's in Library Science (laughs). All I had was this little Bachelor of Science in Aeronautical Engineering at the University of Michigan, which the management valued above hers, you know, her degree from USC. So, I wound up being the last one and I thought, “Well, this is not too bad.” I enjoyed the work. It was fun because I could work with the engineers and a lot of them were like my kids and I knew what they wanted. I understood their language.

Listen to Dorothy describe the changes in the workplace from when she worked shortly after graduation to resuming her career after her kids were grown.

DP: Yes, there were a lot more women. Still overwhelmingly male but I really got a kick out of talking with the gals that came through because I had really been sort of one of the pioneers and now they were coming along and not having anywhere near the nonsense, they didn’t have a typing test. Well, as it turned out, I didn’t have to take it when I went over to apply at General Dynamics either. By that point they had done away with it. Not all women had to take it because there were other women engineers working there. So, progress has been made.

KW: Would you say that discrimination that you felt or saw was definitely disappearing?

DP: There was very little of it but was still some. I remember when I first started there was a very disturbing poster on the wall in somebody’s office that I would always see when I walked down the hall and, you know, it was this girl, this pin-up type bending over, too much showing from behind, talking about getting in your drawers or something. I found it quite offensive and that finally disappeared. But I had one coworker that...it didn’t seem like...no matter how I constructed an English sentence he could manage to find some salacious way of taking it. And I just got to the point where I just avoided him because I thought, "You know, I don’t want to deal with something like this. My mind does not run in those channels. I don't like that kind of thing.” But that was the only person. Everybody else, like the guy that I was assigned to help, became a friend. Many of the others I was quite close to and really enjoyed working with and I was always respected. In fact it was kind of funny. I came in and started learning how to use a computer and there were some of the older guys who had kind of refused it but managed to figure out how to work a computer after that. “This old bat can come in and do it!" (laughs).

Listen to Dorothy discuss age discrimination and describe how her career as an engineering librarian concluded.

DP: I think that would have become an issue if I had stayed in it, but my skills were kind of eroded by that point. I could work with the engineers but I wasn't ready to take on a role as a lead engineer or anything like that or, you know, come up with anything on my own. I could follow what they were doing and help and that sort of thing but I really didn’t have the desire to push myself that much. I wasn’t that competitive. I was happy doing what I was doing and it was the same way with my library job in that I had no political ambitions trying to rise in the company. I was happy to have a job I could do and that I knew how to do and that I knew was productive. And the feedback I got from the guys that I helped, very nice. I was respected. But General Dynamics was bought out by Hughes and we were sent to Tucson and again I was the only librarian from General Dynamics and then I had to work with the new librarians and it was kind of a little different because they had a rather different set-up. We handled many secret, confidential documents and had to have security and they weren’t doing that in their library over there, so there little differences like that. And then when we were going to Tucson...well, let’s backtrack a little bit. Every library I’ve ever worked in has moved and moving a library is not an easy thing (laughs). I had helped move the county library from one building to another and then I got into General Dynamics and I had to move my little library two or three times within the same building and then I had to move back to Pomona when the divisions recombined and then a bunch of stuff came up from Convair that I had to work into it. So, by this time I’d gotten pretty good at knowing how to lay out the library and how to move it. So, when we were moving to Tucson, they came up with this floor plan that was totally unworkable and hard but we did it and sent it back and said, “set it up this way" and then I went to Tucson and lived there for about eight months and pretty largely combined the libraries from Pomona and from the Hughes Division in Northville. Anyway, I got pretty good at that sort of thing, so after I retired from there I had a couple of other jobs working in libraries, just sort of part-time things or short-term kind of things, but always going in with the idea that I was going to organize a bunch of stuff they had. That’s really my strong thing, I guess, is organizing things.

KW: Well, I would imagine a library definitely needs it.

DP: But I retired early from General Dynamics because Bob and I didn’t like being separated; he was here in California and I was in Tucson and flying back and forth every couple of weeks. So, I left there early. It was satisfying because I could finish it up and leave it (laughs). And it had been kind of a bitter pill when they ended our library. And then I know that after I left that they moved the library eventually to some other building. I don’t even know what they did. You put a lot of yourself into building this thing up. I had had the opportunity to start the library at the Value Systems division, which is the new division. I knew that they had moved some stuff over from Pomona but I got an assistant that had an M.L.S. and we were buddies (laughs). We really hit it off and worked so well together. And together we had built that library up and so it was one of these things we had hoped to pass on to other people. It no longer exists I’m sure.

KW: So, when did you officially stop working?

DP: Let’s see it was May, 2002 I guess. I had gone to work with a fasteners manufacturing plant. Bob had gotten a job there. He had worked at Kaiser Steel for years until that place went under and then had several other jobs. And he was working there and they had a lot of reports and things that needed filing and they were just in a mess. They had several different filing systems throughout the plant and so, I don’t know, he talked to the boss about me and the boss said, "Send her in and let her loose” (laughs).

KW: Yeah, “She’s an organization fiend."

DP: Yeah. So, I got that all put together just about the time that the guy had decided it was probably as long as he wanted to keep paying me, it was right about that day. After that I just decided I didn’t really need to work anymore. I was 66 by then.

Listen to Dorothy describe the career of her daughter, a math major from Cal-Poly, and those of her two sons, a mechanical engineer and a financial analyst.

DP: Yes.

KW: Did any of them go on to be engineers?

DP: Oh yes. Our daughter showed a real flair for math early on. She liked it; it was fun and we encouraged that and so when she was growing up I always told her, “Go with your strengths. Get a degree in math or something of that sort then you can have a job where you’re making good money and you’re self-sufficient and all that sort of thing and then maybe you can find time every once in awhile for some of those other fun things that you like." Of course, when you’re working there really isn’t much slack time. Anyway, she got a math degree from Cal-Poly and she went to work for General Dynamics also and she got into computer programming, well they call it "Signatures". Guys would go out and record the infrared signatures of missiles and various tanks and helicopters and all that sort of thing, each one has a unique identifying signature, the waves and all that sort of thing so that you could tell what it is. You program a missile that way, so that it can check out the infrared signature of something and tell whether it’s a friendly or a foe and whether it wants to lock onto it to destroy it or if it wants to let it live. Anyway, she got involved in that, doing computer work on it. Of course, in the big cutback at General Dynamics she lost her job, but eventually she got on at Lockheed, now Lockheed-Martin, Skunk Works in Burbank, which was a secret effort and they had lots of people that were good at radar but they didn’t have anybody that was good at infrared, so they hired her and she met her husband there, an aeronautical engineer, has a master’s degree from Cal-Poly (laughs). He’s from Cincinnati.

KW: Oh, okay. I’m from Ohio originally.

DP: Are you? Oh, okay, well, he got his degree from University of Cincinnati. He's an Ohio State fan in a hotbed of Michiganders (laughs).

KW: My Dad is a big Ohio State fan whereas I root for the Wolverines.

DP: Good for you (laughs). Anyway, she has a little girl now but she has gone back to work full-time because they just wouldn’t let her go. I’m living my career vicariously through her because she has made the career out of it that I never did. But she had gotten very good at it even before she got married and she married kind of late in life, so they only have one little girl. And they were married for five years before she was born. But anyway, Lockheed did not want to let her go; they brought her back half-time for awhile and then finally wanted her back full-time. But she has really made a mark for herself.

KW: I wanted to ask you, I’ve read in articles and I’ve heard it mentioned before that a big challenge facing today’s women engineers is finding balance because they want to be able to have a career and raise a family, how is she managing that?

DP: Well, she is but there are times, you know, she is thinking about possibly trying to leave it because her husband is doing well enough that they don’t really need her income anymore and she’s been thinking seriously now that Clara is five and starting school maybe she ought to stay home so she’s there when she comes home. I don’t know whether she’ll be able to do it or not because I know she also loves her job. But there’s the typical mother’s complaint that she does not get enough sleep. And even though Mike is a terrific husband and a help, has been great with Clara right from the start, it’s still...much of the burden always falls on the woman. He’s a pilot and he likes to go off and fly and all that sort of thing. And she’s a censor, she censors essays...and she has gotten back to that again. She was pretty serious about that when she was in high school. That’s one of her things. She gets out and she’s got a group she plays “Dungeons and Dragons" with that started in college and they still get together (laughs). So, she gets her little outings too.

KW: It must be hard because, like you said, she’s sort of doing double duty.

DP: Yeah. It’s very difficult and she did finally take my advice and get somebody to come clean her house for her (laughs). Because I said, “You can’t do everything." I know when I went back to work I still had two boys in high school and it was difficult to come home and fix dinner and then clean up dinner and it would nine o'clock before I could sit down and look at the paper and by then I’m falling asleep. There just aren’t enough hours in the day and you’re spending all your time getting up and going to work and working and then falling into bed. (laughs) But then, not to leave out the sons, number one son is Mike also, a little confusion there, but he went to University of California, Santa Barbara and he’s a mechanical engineer. He talked about going into aero and when I was there I said, "Maybe you would be better off being a mechanical engineer and don’t overspecialize because sometimes they’re looking for ways to eliminate you when your resume comes in. You might be better off not specializing because aero is a branch of mechanical." So, he did that and he also talked about, “Well, gee, everybody is going into electrical,” and I said, "Yeah, but you’re better off being a good mechanical than a so-so electrical." (laughs) So, anyway he works for the Navy at Point Mugu, which is where Pat worked for a long time and he is in charge of targets, the things they put up for the Navy pilots to shoot down.

KW: What does the last son do?

DP: The third one, Doug, is our black sheep: he’s a financial analyst (laughs). But he likes science and stuff too. He’s a plane nut like the rest of us and he thought for awhile about studying physics, but then he started getting into it and decided that between the physics and the math he was overwhelmed. He’s always liked money (laughs). So, anyway, he’ll probably be able to buy and sell the rest of us. But they’re all technically inclined anyway. In fact, on this cruise our son-in-law Mike found this float plane trip and it turned out that Christy and Mike and Clara and Bob and I and Doug and his friend Caroline all went in this plane (laughs) in the fjords of Alaska, landed on one of them, saw some bears. It was great.

KW: I was actually just in Alaska two summers ago. We did a little cruise there. It was very pretty.

DP: Oh, I loved it. That was the cruise we took, from Anchorage down to Vancouver. So, anyway, they all definitely were college oriented. Doug wound up kind of stringing his college career out because he didn’t want to give up his job is what it was. And he would have to do that if he went to California in Santa Barbara like he was all set to do. So, he wound up going to the local junior college for a little while and then he went to the University of La Verne over in La Verne, California, which is not far from here. I’m sure you’ve never heard of that one (laughs). But anyway he got his degree from there and then he got his M.B.A. at UC Irvine and Mike got his M.B.A. from USC, which we try not to talk about (laughs). They came up to Point Mugu and offered the classes there.

KW: Well, it seems like they’ve all definitely inherited your interest in learning.

DP: Yeah, they have. And of course they get it from their Dad too. He took the professional engineers test after he left his job at Kaiser, when Kaiser shut down the steel mill, and he was working for a testing lab and they said, "Well, it'd be even greater if you had a professional engineer stamp to put on your report," (laughs) so he went out and did that.

Advice

Listen to Dorothy’s advice for young women engineers or scientists.

DP: Don’t let anybody discourage you from it, that’s for sure. I don't know, you know, like I said my career being as it was, if they can stay with it a little longer than I did and establish themselves better. But I never regretted giving up my chance for a career to stay home and raise my kids because I got a lot out of that too.

KW: Right. I would imagine you must be so proud of your children.

DP: Yeah, I am. They’re three productive citizens, never had any trouble with them or anything. I think they turned out pretty well. We were lucky we think.

KW: Well, that is definitely an accomplishment in and of itself that I don’t always think gets enough recognition. My mom stayed home to raise us and she’ll be like, “Oh, I feel bad that I never went back to work,” but she put all of her energy into helping us do well in school, go to college, have a great childhood.

DP: Yeah, I think that’s important. I know Christy had Clara...and that woman has just been great. She has taught her so much. She has structure in her babysitting and things like that. Clara’s a very smart little girl, she has just learned all kinds of things.

KW: Is she showing any aptitude for math or engineering yet?

DP: She is rather mechanical, yes. She likes blocks...I think she’ll be going in that direction. Christy was explaining some math to her, you know, fractions and things like that, just simple little things like when you’re out on a bike ride and Clara wants to know, “How far have we gone?" and she says something like, “Well, we’ve gone a tenth of a mile," and she wanted to know what that meant. She says, "Well, if you take something and divide it into ten things, one of them is one tenth." And then she asked a question later on and it was obvious that she understood the concept. That’s pretty good for a five year old. I can’t remember now what it was, but somehow she managed to add two together or something to come up with a total. (laughs)

2. Dorothy Lewis Patterson, 1956; from her personal collection

Women In Science and Engineering

1140 Undergraduate Science Building

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

ph: 734.615.4455

e: umwise@umich.edu