Sally Farquhar Shumway

Sally earned a Bachelor of Science in Engineering Math in 1947 and an M.B.A. in 1974. She worked at King-Seeley Corporation and Fram Corporation, as an engineering consultant in Washington D.C., and as a supervisor in the Emissions Test Laboratory at Ford Motor Company. While working full-time Sally raised her four children as a single parent.

Growing Up

Listen to Sally describe her family.

SS: Let's see. We lived out in Birmingham, and my dad was treasurer of Burroughs Adding Machine Company which is now part of Excel. So I had math on that side. My mother was an artist, probably one of the world's first feminists. She'd established herself in New York City as a designer, so according to her women could do anything.

KW: Well that's a great attitude to have! Yeah I saw in a survey you filled out, you mentioned that she had actually marched for women's right to vote- is that correct?

SS: That's correct. Down 5th Avenue in 1917 I believe it was. She was quite a gal (laughs).

KW: Did you have any brothers or sisters?

SS: I had a younger brother and a younger sister, they're both deceased.

Listen to Sally discuss how she became interested in engineering.

SS: Well of course through my Dad I always liked numbers. And, somewhere along the line l took an aptitude test- it must have been junior high or early high school- and I did really well in both math and science and terribly in social studies, okay in English. So there was no point in considering a lot of different professions and it was wartime and we were supposed to do something that really mattered and engineering fit the bill there. My Godmother's father had been Dean at the Engineering School at Michigan at one time. I don't remember his name. So there was that connection. So a combination of art and numbers makes engineers right?

KW: Yeah, that's true. Can you explain when you were growing up, what was the sentiment like about women in sciences, or even just women having careers?

SS: Well my mother of course was a feminist but generally women were expected to get married and stay home and have babies. And we all wanted to do that until this darn war came along and there were no men left because of the draft- they were all overseas. And women ran the world I remember my mother in her enormous blue jeans driving tanks to Fort Wayne (laughs) from the Dodge Plant. You know, they did everything. So I think at that point women found they could do things.

KW: Wow that's really interesting.

University of Michigan

Listen to Sally tell her story about enrolling at U of M including her reception by Assistant Dean Lovell.

SS: Oh gee, it was just the only place to go. It being wartime at one point I had wanted to go to California because I'd never been there and I thought U.C.L.A. would be great. But it was just too far from home and I wanted to stay near the family during the war. And transportation was terrible.

KW: Oh really? Because of the war or just in general?

SS: Because of the war. The trains were all troop trains, you rode with the troops and guys weren't any better behaved then than they are now.

KW: That's funny. Did you have to fill out an application? Was there an acceptance process?

SS: Actually I got a scholarship.

KW: How did that come about?

SS: Through the alumni association, I applied for it. My father was totally aghast at the idea -he was a Southerner- and his daughter being an engineer was a little difficult for him. So, Mom said, "Why not apply for a scholarship and then he can't say anything," (laughs). So, I did and that was what happened and they gave me a tuition scholarship. I was going to tell you a funny story. So, my mother and I went up to visit the school and the Dean was out so we went to see Assistant Dean Lovell and he just took one look at me and said, "I don't want any girls in my engineering school."

KW: Oh my gosh, he said that to your face?

SS: Oh yes! This was not uncommon at all. And my mother said, "My daughter has a scholarship to your engineering school."

KW: Oh wow, what did he say then?

SS: Nothing. I mean we just left, the conversation was over. And there actually were sixteen girls that started when I did and by the end of the first year they'd all transferred to other schools. And then Frannie Jenkins- I don't know if you've talked to her, she lives in Ann Arbor, she's married...

KW: Yeah, is it Frances Jenkins Holter? Yeah I talked to her a few weeks ago...

SS: Yeah her sister was good friend of mine, she was in medical school. And she actually married Dean Lovell's son. Not Holter but Fran's sister did. And Fran transferred in junior year. So we did have two of us graduate (laughs).

KW: Why did everybody else transfer? You mentioned that almost sixteen girls transferred. Do you know why?

SS: Oh I'm sure they all had different reasons. Some were up there to meet a guy. And for some it was just too difficult and you know they wanted to belong to sororities and you know party and you couldn't do both.

Listen to Sally describe life in Stockwell and in a League House.

SS: The first couple years I lived in Stockwell known as the Stockyard at the time. And then one summer they closed Stockwell and they moved to a League House, I don't know if they advertise those or not...

KW: Was it in the Michigan League?

SS: No. No these were private houses. Usually they were somebody who had some extra rooms and things were kind of out of control really (laughs). They rented rooms and we lived there, we had no food but the dorms were fairly close. But you know it was kind of a nice arrangement because you had a lot more freedom. We still had to be in at 10:30 at night though.

KW: Oh really? Did men have a similar curfew or was it just women?

SS: Oh it was just women. Yeah the only guys that were under disciplinary-hour type things were the Navy V-12 had to be in by a certain time and then there was a group of Army guys that were totally grounded. They couldn't go anywhere.

Stockwell Hall, circa 1940-19501

Listen to Sally talk about campus life and her favorite activities.

SS: Oh gee we partied (laughs). And we'd go down to the Pretzel Bell (a student tavern) and drink beer and lie about our age just like kids do. l dated. I mean it was pretty normal.

KW: Not too different, it sounds like, from today.

SS: Not really. We played at lot of bridge in the dorm. You know, the experience wasn't so different except we were called the "Vassar of the West" because, you know, there were more women than they were used to having. But there were always enough guys, with the Navy guys, there were enough for everybody to date. We had some wonderful dances with the big bands, Duke Ellington, really it was wonderful.

KW: Can you tell me a little bit about your friends, what your friends were like while you were at U of M?

SS: Well, I think that's why we had the Society of Women Engineers because I don't think any of us really had a lot of friends. Frannie Jenkins Holter was a very good friend at the time. But mostly, l don't know I'm an introvert myself anyway so I was busy doing my other things.

KW: Even though there were few women at the school, in the School of Engineering did you still have...were most of your friends female?

SS: Yeah, I'd say that. And we formed this engineering society (actually the student section had been going from the time I started, it was already in existence). Not very many members. The picture I'll send you, I think there's sixteen women in it. And this was in '46. It built up in the war tremendously. And then after awhile I moved to Washington D.C. and they were just two years into...I think it started in 1951...the national Society of Women Engineers which of course is huge now. But we always joked about the fact that we wouldn't have any friends if we didn't have each other because nobody understood us.

KW: That`s funny. So you kind of helped set up the student section of the Society of Women Engineers, is that correct?

SS: I was President of it for awhile. Fran Jenkins and I used to take turns being President and being delegate to the Engineering Council.

KW: What sort of things did the organization do?

SS: Well we'd meet, we'd eat, we'd (laughs) you know what do you do? Oh we did do things like, I remember one time we put on a program of the Bikini Atoll atomic explosion tests that they did, and one of the guys who was head of it was the professor on staff...I can't remember his name. I can't remember anybody's name, it happens when you get old, but we had a huge program for that. I think we sold out Hill Auditorium. But he was really important and he had all these wonderful pictures of that first explosion.

Listen to Sally describe the different rules and career advice women received at U of M.

SS: Well you couldn't go in the front door.

KW: How did that make you feel?

SS: Well that's the way it was. And you know, we sort of accepted that. You had to fight back about certain things, like of course Dean Lovell and his "no women in my school". My advisor, Dr. Schneiderwind, advised me through the first two years of engineering school getting all the basic classes and then he said, "You should go to Katherine Gibbs". And I said, "Why?" Do you know what Katherine Gibbs is?

KW: Is it a secretarial school?

SS: Right. And he said, "Well, you're doing well. You'd make a great secretary for some engineer." No, you don't get it. I am going to be the engineer.

KW: Wow, it's hard to imagine an advisor just being able to say that to a woman's face now, so that's very interesting.

SS: Oh some of them were bad, some of them were wonderful. A.D. Moore who was the overall freshman advisor watched over all the engineers. He was just great. He couldn't have been nicer. But you know, that's just the way it was. We accepted it because that's the way women had been treated.

KW: It's interesting that, you know, at the same time that you're experiencing this different treatment, like you couldn't use the front door of the Union, you were also saying that women were also beginning to run the United States because all of these men were gone.

SS: That's what happened. That's how women got free, was they had to do it. And they realized they could do it. Someone said, "We came out, why should we go back in?" (laughs). My feeling when l had to go back to work with the kids was that I'd been rescued from the sandbox.

KW: Oh yeah? (laughs)

Listen to Sally discuss the impact World War II had on her experience at U of M.

SS: Right.

KW: I guess you already touched on this a little bit when you said there were fewer men on campus because of the draft. Can you tell me about any other changes, either on campus or in the classroom, due to the war?

SS: Well, we had some strange professors. They didn't always speak English. We had one that spoke Russian very fluently and a little bit of English. He was a basic math teacher. But. l don't know. I think probably they tried to keep the classes as close as possible. It was more...just the attitude toward learning.

KW: What do you mean by that?

SS: We were so serious. That was really important that we do things right. And the war was always there. Somebody always had the news on and a lot of the women in the dorm, particularly, had boyfriends that were overseas in certain areas. And we all knew who did what and what happened and you know, a lot of them were killed. So, yeah it was terrible. It's not like this stupid war. You know and things like, we had food rationing. And you had to turn over your books of food stamps when you went into the dormitory. And my mother got mad because they took out a whole year's worth of coffee and sugar (laughs). And she said, "You're only there 9 months, that's not fair!" But, you know, we just were so serious.

KW: What was the mood like then, when the war was over in 1945?

SS: Oh, there was toilet paper six inches deep down State Street! (laughs) And they locked the Navy up. And the gals, we all stayed out all night. I remember going with a friend of mine. We had a bottle of wine and we went and sat way up on a hill over the river and cried.

KW: Did that same seriousness pervade after the war was over or was it more a sigh of relief?

SS: Well, a sigh of relief and waiting. The guys did come home the year I graduated. I guess it was '46 because l graduated in February of '47. The average age of the freshman class...l mean the senior class was 19 'cause we'd all gone to school all summer and all winter and had a final at 8:00 New Year's Day. See, it was crazy. But then the average age of the freshman class was 22. They were all the veterans, they'd come back. And that really changed the campus tremendously.

KW: Yeah I would imagine. So were you, by the time the veterans were back, were you done with school?

SS: I graduated in '47 and the guys...that was the year they came back, '46. l remember one guy that was having trouble catching up on his math and he'd been a pilot in the war and l tutored him in return for his taking me up in an airplane and flying over Ann Arbor.

KW: That's neat!

SS: Yeah it was. I'd never been up in a plane. And he picked this thing up by the tail and wheeled it out on the runway with one hand (laughs). I thought, "Wow...I don't know if want to go up in that."

KW: Yeah I would feel the same way. That's funny. How did the veterans treat you in your math, science, or engineering courses or just in general?

SS: Well, we weren't in the same classes.

KW: Oh right because they would have been freshman.

SS: Right. I was in one class...I look a class in gyroscopes and there were several Army guys in that but that was during the war still. And they were terribly serious.

KW: Did having all the guys back bring about any changes in your social get-togethers?

SS: Uh not really, most of them were married. Yeah, in 1946 the population went from half married to ninety-some percent married. The war was over; we'll all get married.

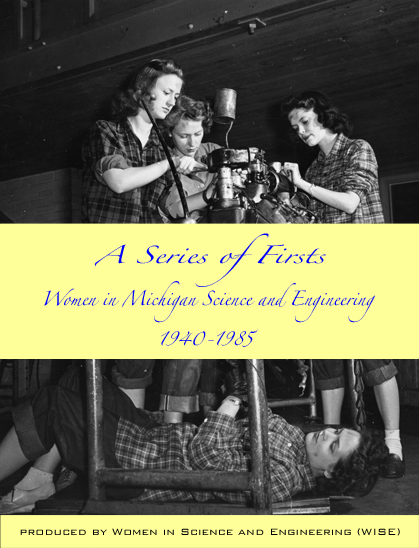

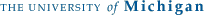

Sally Shumway is third from left, Michigan Technic, 19452

Listen to Sally describe her interactions with her male classmates and professors.

SS: Well, I think the classical comment when l asked one guy why he didn't ask me out for a date...l mean just jokingly because we were good friends...he said, "You know Sal, I never think of you as a girl." And I think that's the way it was. By the time we were there and we proved that we could do the work, they just accepted us.

KW: And you had mentioned a few different professors and your advisor who told you to go to secretarial school. I guess, overall what were the faculty's general feelings about women in the science and engineering? Were they pretty supportive?

SS: Um, it was both. They were either very supportive or very anti. When I took a class in materials engineering, I got to run the crank on the Brinell machine and I got the heaviest hammer (laughs). You know, real subtle stuff like that. But then there was one professor who was from the Philippines who made me his student assistant and he wanted me to come back to the Philippines actually. He'd come over there because his wife was in medical school at Michigan. He said, "You know, we need people to teach in the Philippines." So, you know, you met every kind of reaction. These guys, it was tough on them. They'd always had their school to themselves.

KW: You had mentioned in your survey about being given the heaviest hammer in forging class. You said there was some general, good-natured semi-harassment. What was the best strategy for dealing with that? To just be a good sport...

SS: You laughed at it. I mean it was funny (laughs). There was one guy who put the tail of my shirt in the vice once and of course I half ripped it off (laughs). No, it was all meant well. There were very few guys that were really angry.

KW: Can you tell me about any particularly memorable classes that you took?

SS: Actually, when I took psychology classes over in the liberal arts school. I took a class just for the fun of it. I loved that. I loved all my math classes. Basically, I liked theory. I guess nothing is popping out.

Listen to Sally describe her role models, Katherine Stimson and her mother.

SS: Oh yes, she was the woman I knew in Washington. This is how things were then. She was the assistant for CAB (Civil Air Board) which became CAA (now the FAA). And the man who was head of it was a naval officer who did nothing, so she basically ran the whole thing. And she was a pilot. She was president of SWE national the first year I knew her. And I was...she made me the first head of the membership committee. So, that was the third year that the Society existed. She was a wonderful role model.

KW: Were there any other people that you looked up to during your college years?

SS: Well, there weren't a lot of women.

KW: You had talked about your mother being a feminist. Was that something that, you know, kind of helped you if you ever got discouraged, like her attitude of "women can do anything"?

SS: Yeah. I mean that was just part of who I was. She told me that so many times. She said, "You know you can do anything you please. Just 'cause you're a woman doesn't mean you can't." I did stay home. I planned on staying home with my children and I would have intended to stay home given my choice but I had to go back to work. And I can't tell you how grateful I am that I had that engineering degree and had some experience working at that point. Then I could get a job where I could support my children.

Career and Family Life

Listen to Sally talk about her early career after graduation.

SS: Well, I wanted to stay in Ann Arbor. So, I wandered all over every place I could think of and every place that had an ad. Finally ended up working for the University doing a statistical study...you know it was a thing that lasted until June or something...and then in the fall I went to work for King-Seeley. I don't know is K-S still there? It's downtown. They build automotive gauges for Ford Motor Company. And I worked for them for several years. And then went to work for Fram Corporation, which was in Dexter. They had a big lab there and I worked in their dust tunnel. Again it was still in automotive work. That's where l met my husband.

KW: Was he also an engineer?

SS: Well, he had an engineering degree but he was salesman. He was transferred to Washington. D.C., so I went down there for two years and I worked for a consulting engineering firm there. Then we did wonderful work. We had one of the world's first computers: a big, old analog thing. Oh, it was more fun than at barrel of monkeys because my job was to take these performance curves from aircraft engines and convert them into mathematical formulas. Oh, that was fun (laughs). After two years he was transferred to New England and I said, "I'm not going, I like what I'm doing here" (laughs). So, for six months he commuted back and forth to Washington. Finally I broke down, "Okay. we'll move." (laughs) So, we moved to Rhode Island; he was still working for Fram all of this time. And I stayed home and had four kids. And then he became mentally ill, completely incapacitated. And he, of course, died not too long after. But at the time I had no other source of income, so I tried looking for jobs in Rhode Island and got nowhere until one day I got a call from one of the men who worked for Fram in Rhode Island and he said, "Can I stop by on my way home from work?" I said, "Sure" and he offered me a job and I had no choice; I took it. And I stayed there for three and a half years. Then my sister sent me an ad from Ford Motor Company and they were looking for someone to help set up a test facility because emissions were becoming a big thing at that point. So, I applied for that job and got it.

KW: Was that your last job then?

SS: Yes, l stayed at Ford for twenty years.

Listen to Sally describe how she juggled her career and her children.

SS: Yes. The oldest was seven, the youngest was two when I went to work (laughs).

KW: Oh my gosh, what was that like?

SS: It was crazy (laughs). I had a wonderful woman that just came in and she was there all day long. I'd get a student to live in, give them free room and board in exchange for helping me out, picking up the daytime babysitter. And, you know, it all worked.

KW: Yeah, you managed to juggle it all.

SS: Yeah. And my kids have done okay. You know, none of them have really suffered much as a result of this kind of an upbringing. In fact one of them is an engineer. She's the vice president of a company in Boston. And one is a producer for television in Dallas and one of them has six kids and she can't get out of the house (laughs). And my son lives here in Tucson and he's a mortgage broker.

KW: Well yeah, it sounds like they have all done wonderfully.

SS: Well yeah, I'm very proud of them all. Three of them worked their way through college and the fourth one had six babies.

Listen to Sally talk about moving to Tucson and how she began another career as a tax preparer.

SS: I remarried a man who helped me raise my kids. He was a wonderful father to them and he died of a heart attack. So, after l retired in 1986, I moved to Tucson. One of my daughters and I had been down here on a camping trip and I looked at that blue sky and l said, "You know, after years of Michigan's gray skies, I'm moving down here." (laughs) And five days after I retired, I was on the road for Tucson. I'd been here a couple months and started getting bored and I saw an ad for H&R Block looking for people to do taxes and I thought, "What the heck, why not?". So, I took the class and became a tax preparer and then I became manager of one of their offices and at an office manager's meeting I met this nice guy and we were married in 1989 and we're still married and still happy.

KW: That's great to hear. It's funny that you mentioned Michigan's gray skies because we got a lot of snow yesterday.

SS: I remember that the Ann Arbor winters were just brutal. I had a raccoon coat I used to wear to keep warm and I'd ride my bicycle in this raccoon coat (laughs).

Sally Shumway, 19463

Listen to Sally discuss how she avoided becoming a victim of hiring discrimination.

SS: By the people I worked with, it was fine. You had to be careful with the companies. I had a policy at Ford of never accepting a move to a new job that had not been filled by a man because it was the time when they were satisfying the requirements for women in management and things like that and l never wanted to be a statistic. I wanted a real job. And I had a very supportive manager there. I was supervisor of two different groups. One group wanted to call me "Mom" (laughs). I said, "Absolutely not! I am not your mother!" Oh, they were just teasing, you know, we did well.

KW: So, you'd say overall it was a pretty positive experience, nothing sticks out in your mind besides what you mentioned...just outright discrimination? You know in undergrad you said you had professors coming up to you and telling you to go to secretarial school but you never really experienced that in your career?

SS: Um, I experienced a bit of it. At one time l wrote an SAE (Society of Automobile Engineers) paper that was given at an SAE meeting in Detroit when I was working for Fram. It was on the test project I'd done on radioactive bearings there in engine wear and they wouldn't let me sign my name to the paper, so my boss signed his name. And I was not even allowed to go to the meeting because they didn't want that image. I don't know if you've been to SAE meetings but they do have the women in the low-cut evening gowns and the girly things and they said, "We don't want any part of that." I'm not part of that (laughs). No, it was generally, people accept you for who you are as long as you do the job.

Advice

Listen to Sally's advice for young women engineers.

KW: Just a few last questions. What sort of advice would you offer to women entering the engineering field?

SS: Go for it. If that's what you want to do and that's what you have the skills for there's no reason in the world not to do it. It's a wonderful field; it has all sorts of latitude and different areas you can go into. I'm very glad I spent all those years working in engineering.

2. Michigan Technic, April 1945, cover

3. Michiganensian, 1946, p. 205

Women In Science and Engineering

1140 Undergraduate Science Building

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

ph: 734.615.4455

e: umwise@umich.edu