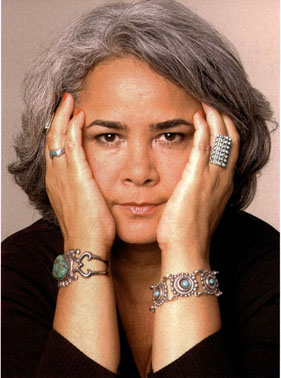

Esmeralda Santiago was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico and lived there until she was thirteen years old. In 1961, she moved to the United States. She was the eldest in a family that would eventually include eleven children. Santiago attended New York City’s Performing Arts High School, where she majored in drama and dance. After eight years of part-time study at community colleges, she transferred to Harvard University with a full scholarship. She graduated magna cum laude in 1976. Later, she earned her master’s degree at Sarah Lawrence College and was awarded honorary doctorates from Trinity University and Pace University.[1]

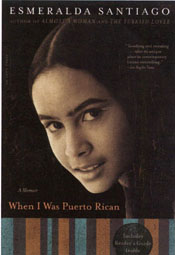

However, Santiago’s success did not come easily. She faced discrimination and economic instability as a newly arrived immigrant. She also helped to support her mother and siblings. Her dream was to fulfill herself as a woman and a person, discover her identity, and find her calling. She describes her experiences in her first book, When I was Puerto Rican (1994), her second work, America’s Dream (1996), and Almost a Woman (1999). The themes in these works include immigration, Puerto Rican identity and self-discovery, the shift to new culture, and acceptance of a bicultural, multiethnic and bilingual model. The retelling of her memories has made her an inspiration to women in search of their identity and for Latina/o readers who struggle to assimilate into American culture without giving up their traditions and language.[2]

Santiago’s work is part of the autobiographical narrative movement. She narrates her experiences from her own subjective point of view and describes a process of searching for personal identity. She also uses language as a way of expressing self-awareness[3]:

“I didn’t report the time I was chased from the subway station to the door of the school by a woman waving an umbrella and screaming, ‘Dirty spick, dirty fucking spick, get off my street.’ I never told Mami that I was ashamed of where we lived, that in the Daily News and the Herald American, government officials called our neighborhood ‘the ghetto,’ our apartment building ‘a tenement.’ I swallowed the humiliation when those same newspapers, if they carried a story with the term 'Puerto Rican' in it, were usually describing a criminal. I didn’t tell Mami that although she had high expectations for us, outside our door, the expectations were lower, that the rest of New York viewed us as dirty spicks, potential muggers, drug dealers, prostitutes.”[4]

This quote reveals the discrimination that Santiago experienced during her adolescence and the way in which she chose to deal with her emotions and the injustice. It also speaks to Santiago’s development of identity. She is aware of the negative connotations that accompany identifying as Puerto Rican in her new home, yet she keeps this knowledge to herself, pressing onward and fulfilling her mother’s expectations. These slurs and stereotypes that Santiago encountered motivated her to work even harder not only to prove others wrong, but to prove that she was capable of greater things to herself. Discrimination is a reoccurring theme in Santiago’s work and takes shape in many of her memories.

The combination of living in an urban environment, a mother who spoke little English who could not find work that would pay enough to support eleven children, and being the eldest, Santiago endured a lot of pressures inappropriate for a young adolescent. Santiago describes having to go to the welfare office with her mother:

“When Mami was laid off, we had to go on welfare. She took me with her because she needed someone to translate. Six months after we landed in Brooklyn, I spoke enough English to explain our situation. ‘My mother she no spik inglish. My mother she look for work evree day, and nothin. My mother she say she don’t want her children suffer. My mother she say she want work bot she lay off. My mother she only need help a leetle while.’”[5]

This scene depicts the instability in Santiago’s life as a result of the migration from Puerto Rico to New York and confirms that, “Migration frequently wreaks havoc on the traditional family organization in Hispanic culture. Authors reflecting their own experience, displace the typical ‘central patriarchal figure’ and, instead, depict ‘a woman-headed and woman-populated household’ (Horno-Delgado et al., 1989a, 12).”[6] The quote shows Santiago’s mother as the head of the household struggling to support her children or the displacement of the typical “central patriarchal figure”. The use of broken English serves to further emphasize the hardship and humiliation that Santiago experienced. The effects of the displacement of the typical patriarchal figure also help in the development of Santiago’s identity in the novel. She becomes increasingly independent, helps to support her family, and strengthens her identity as a woman:

“They spoke English to each other, and when they talked to us or to their mother, their Spanish was halting and accented. Mami said they were Americanized. The way she pronounced the word Americanized, it sounded like a terrible thing, to be avoided at all costs, another algo to be added to the list of ‘somethings’ outside our door.”[7]

This quote demonstrates the difficulty in shifting to a new culture and the resistance to accepting biculturalism. To be American is seen as a betrayal to their roots, according to Santiago’s mother, yet outside of their home, Santiago is told that to be Puerto Rican is a disgrace. These contradicting messages reveal the struggle to assimilate into her new home. The difficulty of finding the right balance of Puerto Rican culture and American culture is a reoccurring theme in Santiago’s work as a result of living in an urban space. She is struggling to survive in an environment that does not welcome her, to help support her family and to succeed. However, these things require her to assimilate contrary to her mother’s beliefs.

The theme of assimilation and acceptance of a new culture appears again:

“There were two kinds of Puerto Ricans in school: the newly arrived like myself, and the ones born in Brooklyn of Puerto Rican parents. The two types didn’t mix… To them, Puerto Rico was the place where their grandparents lived, a place they visited on school and summer vacations, a place which they complained was backward and mosquito-ridden. Those of us for whom Puerto Rico was a recent memory were also spilt in two groups: the ones who longed for the island and the ones who wanted to forget it as soon as possible.”[8]

Santiago illustrates the division between the urban space of New York and her place of origin as well as the division between newly arrived immigrants like herself and those that have already assimilated. Those that have already assimilated or were born of Puerto Rican parents view Puerto Rico as something of the past. Santiago struggles to fit in with the “Brooklyn Puerto Ricans” and embrace both the old and new, a common issue faced by immigrants.

Esmeralda Santiago uses her experiences as an immigrant in an urban space as inspiration for much of her work. Her memories as a working class immigrant, the awful housing conditions, lack of work, difficulty in assimilating and determination to succeed sometimes appear to be the stereotypical Puerto Rican immigrant story, however, they are brutally honest. Santiago’s experiences of discrimination and instability added greatly to not only her identity but her writing as well. It is because of the documentation of her struggles that she has made an impact on countless women also in search of their identity and for Latina/o readers attempting to assimilate into American culture without giving up their own culture and past.