For diners in eighteenth-century England, the cultural customs of dining were the focus of the meal. For an upper-class individual, there were cultural rules that dictated everything from dressing for the meal to leaving the dining room.

Upper-class women could spend over an hour dressing for dinner because it was customary for women to change their entire outfit for the evening meal [1]. The elaborate dinner dress consisted of a corset, a bodice, stockings, a petticoat, a gown, ruffles and shoes [2]. Men also would spend time preparing for dinner. However, it would not take men as long because, in most cases, they only repowdered their hair [3]. Dress for dinner was important because young men and women looking for a companion used dinner parties as a way to meet and court potential mates.

After

preparing for dinner, guests would proceed into the dining room.

Following an elaborate ritual, the host of the dinner would enter first

with the most senior lady. The host would seat himself at the foot

of the table and, later, when the hostess entered the room as part of the

procession, she sat at the head. The senior lady was first to choose

her seat. After the senior lady was seated, the remaining guests

were free to choose their places at the table. Most likely, the senior

lady would sit near the hostess because the seats near the hostess were

places of honor and reserved for the most important guests. The same

number of male and female guests rarely were invited to dinner, and each

person could choose with whom they wanted to sit. There was no specific

placement for the guests at the dinner party. Consequently, this

arrangement was favorable to courting because the guests could choose their

seat mates

[4].

After

preparing for dinner, guests would proceed into the dining room.

Following an elaborate ritual, the host of the dinner would enter first

with the most senior lady. The host would seat himself at the foot

of the table and, later, when the hostess entered the room as part of the

procession, she sat at the head. The senior lady was first to choose

her seat. After the senior lady was seated, the remaining guests

were free to choose their places at the table. Most likely, the senior

lady would sit near the hostess because the seats near the hostess were

places of honor and reserved for the most important guests. The same

number of male and female guests rarely were invited to dinner, and each

person could choose with whom they wanted to sit. There was no specific

placement for the guests at the dinner party. Consequently, this

arrangement was favorable to courting because the guests could choose their

seat mates

[4].

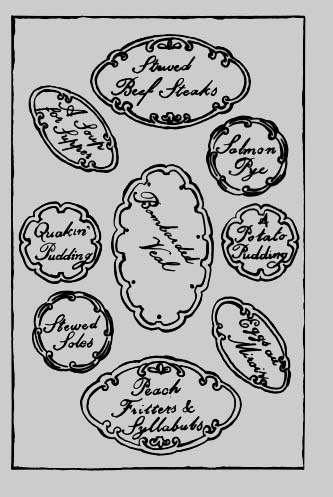

Every meal consisted of two courses and a dessert. However, a course in eighteenth-century upper-class society consisted of between five and twenty-five dishes. In one course, soup or creams, main dishes, side dishes and pastries would be placed on the table all at once. Unfortunately, this type of presentation meant that by the time the guests finished eating the soup, the other foods had to be eaten cold [5]. The dishes were placed on the table with a certain balance. In the center of the table meat dishes were placed, while accompaniments were placed on the sides and corners. On one end, the soup was placed and on the other, the fish would be placed. Vegetable, fish or custard dishes were never placed at the center of the dinner table [6].

An example of the appropriate places of the dishes

for a course, (Black, The Jane Austen Cookbook, p. 15)

Eating would begin with the host serving soup to the guests

[7]

. After

the serving of the soup, guests would begin “taking wine” [8]

with each

other, which meant toasting to each person’s health

[9].

The host

then would carve the large joints of meat which replaced the empty soup

tureens. After the initial carving, each gentlemen would serve himself

a portion of the dish in front of him, and then offer the same dish to

those around him. If the gentleman wanted to eat from a dish located

across the table, he would send a manservant to bring the dish to him.

Although there were many dishes on the table, each person was to chose

two or three dishes he preferred and eat only those things

[10].

When the second course was served, new dishes, new utensils and a new table cloth were placed on the table. The second course consisted of as many dishes as the first. However, the dishes for the second course were lighter, with accompaniments to the meats such as fruit tarts, jellies and creams. To accompany the first and second courses most guests drank wine, beer, ale, soda or water. However, some gentlemen preferred to drink port or sherry [11].

After the second course the table cloth was removed and dessert was served. Dessert usually consisted of food that could be eaten with the fingers such as dried fruit, nuts, small cakes, confections and cheese [12]. With dessert, the gentlemen would drink port and the ladies a sweet wine [13].

At the conclusion of dinner, which lasted approximately two hours [14], each guest was served a glass of wine. After drinking the wine, the hostess would rise and a gentleman would open the door to the dining room. The women at the dinner party would follow the hostess’ lead and exit to the drawing-room, leaving the gentlemen to drink and converse [15].

Consequently, it can be seen that the cultural customs of dining required

considerable effort. These customs established upper-class standards

which set the upper class apart from the lower class. However, as

for the food dishes themselves, most English people preferred to combine

urban and rural food styles which were similar in all social classes

[16].

The cuisine which women cooks prepared for upper-class dinner parties was

based on a British cuisine that was “socially homogeneous.”

[17]

The absence of a firm distinction between upper and lower class cuisine

and the mediocrity of the food itself, as described on the types

of food link, illustrates that cultural customs were the most important

component of an upper-class eighteenth-century dinner.

Click here to Return to the Main Page