"You cannot take too much pains to maintain subordination

in your corps."

-F. Grose, Advice to Officers and Soldiers

of the British Army, 1801

"…the state offered every

inducement in the way of monotonous diet, monotonous occupation, climactic

discomfort, bad housing and abundant alcohol that could lure men to

drink; and then deplored the drunkenness of the Army."

-Sir John Fortesque

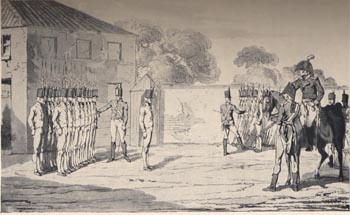

Licking the raw recruit into shape

Satirical sketch by Bunbury, 1780 (Turberville

483)

Daybreak.

Drummers and buglers deliver the "Reveille" call through the

main streets of the garrison camp, and the squadron slowly rises in the

darkness of the barracks. Before breakfast, as cavalrymen muck out the

stables, you and the rest of the infantry engage in a 'smartening-up'

footdrill. (Frey, 95-96) After a simple breakfast between 7:30 and 8:00

AM of dry bread and boiled beef or broth, you prepare for a day replete

with repetitious drills and exhausting marches. (Brereton, 36)

These parades not only to standardize the particular stiff-legged march-steps

of the British infantry, but serve as principal means by which to establish

strict, hierarchical discipline necessary for an efficient and effective

army. A grumbling drill-sergeant presides over the first drill of the

day, tapping his long cane menacingly.

"Character, lads, character."

While "character" is the repeated credo, "subordination"

seems a more accurate term for the sergeant's principal goal. Officers

are committed to the construction of a completely obedient, loyal, and

deferential force. (Frey, 98-99)

Soldiers Drilling: Late 18th Century,

Aquatint, artist unknown

(Dewatteville, 93)

At 12:30 PM, you return to the barrack to prepare supper-your second

and final meal of the day. Since the 'tattoo' call is not sounded until

9:30 PM and 'Lights Out' at 10:15 PM, you'll want to make this meal count!

Again, the menu is limited: bread with stew, broth, or boiled beef, and

the occasional block of cheese. (Brereton, 38) These fabulous dishes and

more can be found in the unauthorized Soldier's

Cookbook.

The second half of the day is usually more of the same-two-hour drills

(up to three in one day), plus dreaded 'fatigue duties.' On a given day

you can be responsible for anything from chimney sweeping, snow shoveling,

cartridge building and packing, and, worst of all, guard duty. (Frey,

94)

This dreary work, performed with only tomorrow's breakfast (still 19 hours

away) to look forward to, drives you to frequent the sleazy taverns and

'grog shops' set up around the barracks by civilian contractors, and imbibe

the 5 pint daily ration of beer allotted to each soldier. Who can blame

you?

The officers decide to give you and your fellow grunts a free evening, and you have a choice: spend it learning the art of military hair-dressing, or go off to the grog shop?