Childhood and Other Neighborhoods & Coast of Chicago

"...and when I came to my stop on Twenty-second Street this time it was easier to imagine how it would have looked to her-small, surprisingly small in the way one is surprised returning to an old grade-school classroom."Stuart Dybek - Coast of Chicago

About Stuart DybekWriting and Style

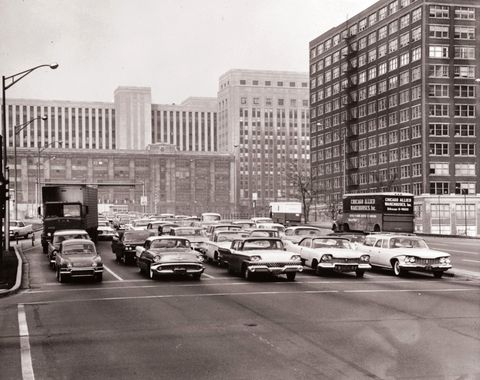

A quote from Rainer Maria Rilke introduces Stuart Dybek's Childhood and Other Neighborhoods. It begins, "Who'll show a child just as he is?" In Dybek's tales, children's explorations of junkyards, dingy shacks, and viaducts are combined with mystical, legendary, and religious undertones. His style of writing is refreshing and optimistic in a Chicago formerly dominated by naturalism - a Chicago where the grittiness of the city consumed the people. Alternatively, Dybek's characters feed off of their surroundings. Stories like Blight focus on the lives wedged between dumpsters and factories. Dybek's characters look adoringly at a sign that proclaims their insignificance and respond, "That way to freedom!" The stories which range from the 1950's to the 1970's, identify children as creators. They are capable of viewing their world (their neighborhood) as they wish. The writing style suggests an infatuation with vibrant sounds and music, especially jazz music. Characters howl like old blues musicians and bridges appear out of texts. Another theme that dominates Dybek's writing is religion and the church. Saintly figures seem to appear in the most mundane of settings. Overall, Dybek's writing is enthusiastic and exuberant. When characters return to their old neighborhoods, they don't cry, they dream nostalgically.

Street Vendors and Guardian Angels Trans-Migration and Religious Figures

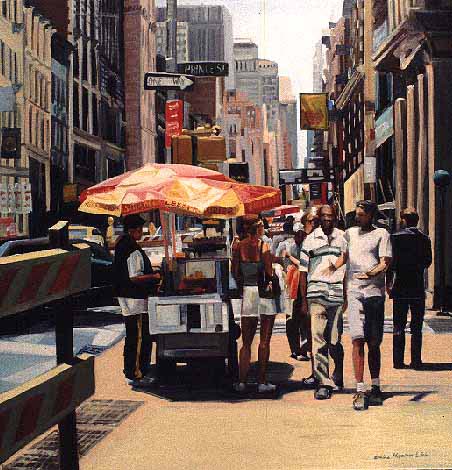

In stories like The Palatski Man, The Wake, and Blight, characters wander into unfamiliar territory and experience revelations. Dybek portrays the neighborhood as the world and its residents are capable of biblical feats. Dybek's characters are routinely affected by religious dynamics, and these thoughts seem to easily translate into their daily lives. In The Palatski Man, Christian images and names are scattered throughout the opening paragraphs. The protagonist Mary relates the lashing of Christ to her own suffering at the hands of Leon Sisca, a neighborhood kid. When Mary purchases a palatski from the holy street vendor, she bites into the honey smothered wafers and thinks of Holy Communion. Perhaps the most symbolic aspect of the story is Mary and John's encounter with the Ragmen. They travel to an unknown neighborhood and become initiated to the lives of street vendors. Mary's revelatory transformation later in the story represents exiting childhood innocence and entering, inevitably, into the fallen world of adults.

The Wake similarly tells a story in which familiar faces experience religious and mystical transformations. On her way back from the funeral home, Jill wanders into an alien neighborhood and loses command of her surroundings. She eventually sees the familiar sight of the neighborhood street vendor, and desperately goes to him in search of refuge from the gang of kids accosting her. Her faith and trust in him is absolute as she conceals herself in the rising steam of hot tamales and heated buns. In this scene, the Hot-Tamale man and his recognizable cart become Jill's only protection, her savior.

Dybek's humorous and refreshing dialogue is most evident in his story Blight. Three teenagers who live on the South Side of Chicago explore their neighborhood in search of beauty, music, and adventure. They revel in the happenings of their home, an area described as an Official Blight Zone by Mayor Daley - a place inhabited by factories and industrial waste. The tales of Ziggy Zalinski, Pepper Rosado, and Dave detail the lives hidden between those dumpsites and urban sprawl. The kids encounter the segregation of Douglas Park, the viaducts separating white from black. Religious themes are also prevalent in this story. Ziggy talks to saints and the Virgin Mary, and they respond. The most dramatic religious image in this story correlates to Dave's leaving and return. Dave leaves his neighborhood, reminiscing of childhood memories and adventures, but when he returns, he is a new man. He has also experienced a revelation of sorts, a transformation into adulthood. But at the end of the chapter, he grows nostalgic. Memories and images flood his brain and he realizes that childhood is a mystical blur, a series of frontiers and mishaps, something that, inevitably, should be venerated.