Margaret Barson Frank

Margaret graduated in 1946 with a Bachelor of Science in Chemical Engineering and completed a Master of Education at Eastern Michigan University in 1973 in Secondary Education and Math. She worked as a chemical engineer in the pharmaceutical industry and as a high school algebra and geometry teacher. Margaret has four children.

Growing Up

Listen to Margaret describe her immigrant family and her childhood during the Great Depression.

MF: Well my parents were immigrants from Transylvania. and I grew up speaking Romanian as my first language. I went to kindergarten when l was four in Detroit and learned English very quickly I gather.

KW: Yeah I was going to say that it wasn't very difficult for you to transition to English?

MF: Not to my knowledge. Not that I can recall. My parents were very education-minded although they hadn't gone past the sixth grade for my mother. and maybe not even the eighth grade for my father. But they felt education was very important and I can recall a blackboard easel with the alphabet and other items on it at home. I think we were being introduced to it although my parents were not that fluent English speakers. Sol started school in Detroit, and between my sister and I, I think we counted ten schools before we got to high school.

KW: Oh wow. Were they all in Michigan?

MF: All in Michigan, yeah. All in same the metropolitan area. We were born in Pennsylvania and moved to Michigan when I was about three.

KW: What did your parents do for a living?

MF: Well my dad Worked at Ford in the foundry and found out that it wasn't good for his health and he switched over to Kelsey-Hayes Wheel Corp. and this was during the Depression era so he was out of work a lot. Anyway, my mother worked outside the house cleaning. So I see the current immigration doing the same, being replicated. It was during World War ll, she got a better job at the Ford Motor Company, still in maintenance work and she had been working for the public schools, so they were working to support our future education.

KW: What was it like growing up in the Depression?

MF: Well. we always had a large garden next to our house that we had rented then bought. So food-wise I never really gave it a great deal of thought although my parents, my mother. did qualify for food supplements from the government. I remember going with her and picking it up with a wagon and walking home about a mile. But I was acutely aware that my parents were speaking with an accent and we were living in a mixed ethnic neighborhood in Dearborn finally. There just seemed to be a little difference there because they weren't really that integrated in the neighborhood, and l think they were more acutely aware of the financial position than I was as a child. And well, when you have one dress to wear on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and another dress to wear on Tuesday and Thursday to school, it didn't bother me, but I was aware that were other welfare children who were wearing items that were made available for welfare families. So I had that kind of frugality during growing up.

KW: Did your family ever experience any out right discrimination or different treatment being immigrants living in Michigan?

MF: Well it was difficult to ascertain that because my mother would attempt to get a job and for instance they had sewing positions open during the Depression- programs the city of Dearborn was running. Although she had always had a sewing machine and could sew, she didn't get it. And we never could figure out why- if it was an ethnic thing or what. It just was in the back of our minds.

KW: I've taken a couple of psychology classes and they always talk about that, that minorities of any kind, it's always in the back of their mind is an idea of is it because I'm a minority or is it because I'm not qualified. So, that's interesting that you say that.

Listen to Margaret talk about how she became interested in math and science.

MF: Well actually, I was more interested in math. I know it seemed to me that in junior high school that my science teacher, Mrs. Woods, seemed to pay a little more attention to me. And I wasn't quite understanding why because I never thought that I was that distinctive in the class. But when I got to high school my math teachers seemed to be quite supportive and helpful and I can't quite say which way (laughs) but I think they were encouraging. Suddenly I can recall going into the trigonometry- and then by that time we were being coached into figuring out what we were going to do because it was obvious that I was going to be going to college- and l know my geometry teacher tried to discourage me. He had been a chemical engineer and he was teaching high school geometry and discouraged me about going into engineering.

KW: Do you remember why?

MF: No. I couldn't figure out why (laughs). I couldn't figure out why. My chemistry teacher was wonderful- he was very encouraging about...I think that's where...and the physics, not so sure because in the physics class, he really didn't want any girls in the class. Mr. Jennings, that is what his name was...so I just kind of felt like it was easier not to be...to just kind of sink into the background (laughs) and not get too involved with anything there. So l think it was really between math and chemistry and my chemistry teacher that I thought I should consider going into chemical engineering. I can recall that.

KW: Can you explain at all, if you had any idea at the time, of the general sentiment about women pursuing science and math while you were growing up?

MF: Well you know those were the days when you'd read Marie Curie articles and books about her and it just didn't feel that it was that...there were more and more women and it felt like "gee that sounds like a goal", to get involved like they did. But no, I don't really recall- other than my geometry teacher trying to me discourage me from thinking about going into engineering. But that's all I can recall.

University of Michigan

Listen to Margaret discuss her decision to enroll at U of M.

MF: World War ll.

KW: World War II? Can you tell me about that?

MF: I got a scholarship when I graduated from high school to go to the junior college t they had established at Dearborn. At the end of the first year, all of the fellows were we drafted so that there weren't enough students to continue the junior college. And I had to figure out where to go. I decided to go to the University of Michigan. My sister was going to Michigan Normal and I didn't want to go there. And I didn't want to go down to Wayne State. I thought it would be quite an adventure to go to the University of Michigan because it was so prominent. So I did.

KW: Oh well that's great. How did your friends and family feel about you going to U of M?

MF: Well, my mother and dad were very supportive. I had been working part-time since the age of thirteen and trying to build up an educational fund which wasn't very large to tell you the truth.

KW: So you were able to use some of that money towards your education at U of M?

MF: That's true.

Listen to Margaret talk about living in Stockwell, Mosher-Jordan and a League House.

MF: The first year I lived in a League House on Washtenaw Avenue which no longer exists- it's a parking lot. I remember the number, it's 1333. I have a daughter who lives in Ann Arbor with her family so we yearly return back and since she's in Ann Arbor it's interesting to see the changes.

KW: I would imagine. Do you remember any of your other living arrangements while you were at U of M?

MF: Well my first year I lived in the League House as I stated and then I spent a summer at Stockwell Hall. And from then on I stayed at Mosher-Jordan Hall.

KW: Yeah I lived in Stockwell my freshman year.

MF: The thing I remember about Stockwell is that the Engineering students who were taking surveying courses would line the hill working on their measurements. That was always kind of a joke. I liked Mosher-Jordan and I think I had a single room on the fifth floor, so it was only a problem when the elevators didn't work, which was frequent. But that wasn't insurmountable. I remember them locking the doors at 10:00 and I'd be on campus in the engineering building with my team doing some experiments because the water pressure was only good in the evening for us to do it. And the house mother would save my meal on a tray and open the door for me to come in (laughs).

KW: Oh geez, that's great! It was only women, correct, in Stockwell?

MF: Yes.

KW: Did you know what they were studying? Do you remember just a general idea? Were you really the only engineer living there?

MF: Yes. At Stockwell I was the only engineer. In Mosher I was the only engineer. I had friends who were in accounting and English and other fields but no engineers.

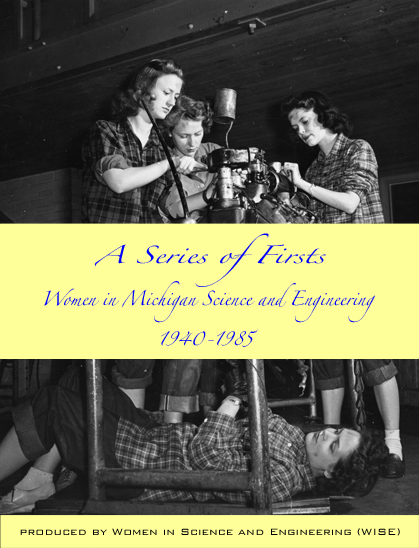

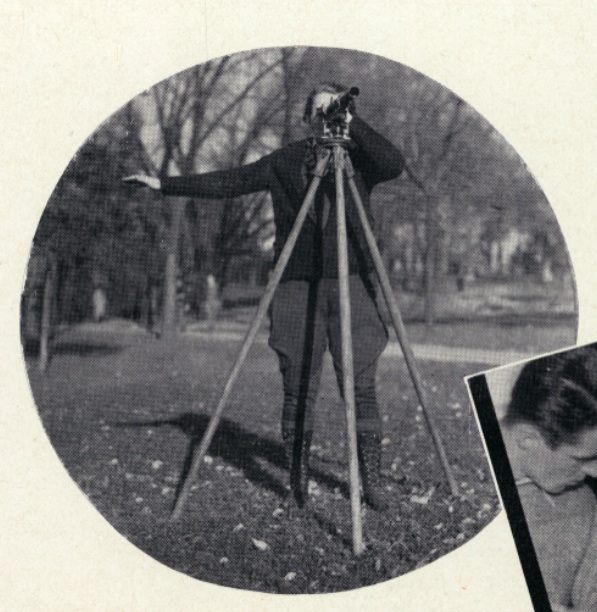

"Something a bit unusual, a girl surveying."1

Listen to Margaret describe campus life including her friends and favorite activities.

MF: I don't know. But I found the engineering school quite...it kept me quite busy at times (laughs). And I did work part-time in the engineering department correcting papers. Dr. York and Dr. Bankero I remember particularly. I can't remember the instructor's name but I prepared specimens for the metallurgical department. I found a lot of things to keep me busy. I did picnic occasionally with friends and there were League dances and dances at the Union. I just never felt I had any time that I wasn't doing something.

KW: I completely understand. This question always makes me laugh because I think it's still the same today. I do homework on my weekends and my days off. Students, I think, are still really busy. I don't know how much that has changed. Can you tell me a little bit about your friends at U of M?

MF: Well I went to school, in those days there weren't many women. There was one, her name was Norma Altman Posner and unfortunately she is deceased. She graduated first in the chemical engineering class. That was very impressive. We had a few classes together. The professors, I always felt, took role by counting how many sailors there were because the University had the sailor program at that time. the naval program. And how many civilians and then how many women (laughs). And so I always thought it was the short-cut way of taking roll call. Let's see, you were asking me about my friends. Would that be in the engineering school or other...

KW: Well I guess overall, did engineering give you a lot of male friends then since you were one of a few women?

MF: Well one of my...when I look back on it see I was sixteen years old when I started college so I was a little on the young side. l just never...l know there were helpful male friends but not what you might be considering...you know, getting chummy and all that, no. I think I was quite a reticent young person.

KW: We sent you a survey maybe a year ago and you mentioned some clubs that you were in on campus. You said there was a rifle club, I believe?

MF: Oh yes there was a rifle club in the lower level of the women's athletic building down by the tennis counts that were downhill from Mosher-Jordan. I don't know. I assume the building is still there. And I think l was in the Junior Girls play.

KW: Yeah I have that written down too. Was that a good way to make friends would you say?

MF: It was enjoyable. It was hard to make time for some of these things. But I felt it was something that one should take advantage of and do. And then the Society of Women Engineers, of course.

KW: What was that like at the time?

MF: I can't quite recall what we specifically did other than have meetings. But I don't think we really did anything because I think we were all so busy with our work. So I think it was more of a camaraderie and a support group.

KW: Did you guys meet in the League, by any chance, do you remember?

MF: I can't recall where we met.

KW: That's ok. I was just asking because I know that for awhile the Michigan Union didn't allow women or they would have a separate door for women.

MF: Oh yes the side door.

KW: How did you feel about that at the time?

MF: Amusing. I thought it was an anachronism, I just thought "how weird".

Rifle practice, circa 19502

Listen to Margaret discuss the impact World War II had on campus.

MF: Yeah it seemed to me...I think they lived in the West Quad or something. But there were a lot of sailors.

KW: I guess just to wrap up with the war, do you remember off the top of your head any other changes you noticed on campus or in the classroom because of the war?

MF: Not that I can remember in the classroom.

KW: What about on campus?

MF: I really wasn't that involved. Other than not seeing a sea of white uniforms, that's about it. But sometimes I felt that they had perks that the rest of us didn't have but I don't remember what they were (laughs). It's just a sensation or a remembrance.

Listen to Margaret describe how her male classmates and professors treated her.

MF: Politely. But there didn't seem to be a lot of camaraderie. The Navy fellows seemed to he quite cliquish and there'd only be it couple of what we called civilians. There just was a separation of everybody in class, there wasn't any cohesiveness of the class as I remember it.

KW: How did the professors treat you?

MF: Very kindly. I think sometimes I felt that they might have realized l was quite young. But, did I say that I worked at the office of Dr. York and Dr. Bankero, chemical engineers, and everybody was very polite and very helpful.

KW: So you never really encountered anyone who, either a classmate or a professor, who said "why are you here, you're a woman, this isn't your place" or anything like that?

MF: Yeah I had that happen back in high school (laughs). I never had it happen again.

KW: So you would say it wasn't really that strange to be the only woman or one of few women in engineering class because everyone just kind of maintained separation...

MF: Yes because, because of the way the class, with the naval presence it seemed like... I think they were all helping each other too which was understandable. Everybody else was more or less separate.

Career and Family Life

Listen to Margaret talk about her first job after graduation.

MF: Well I'Il tell you before I got out of school. Before World War II was over, I was a junior, I was being interviewed by the oil companies, by Hubbell Oil Company in particular and another one from Texas to come down and work when I graduated because they were looking for chemical engineers. Their engineering staff had been compromised, you know, with the draft and all that. And our professors were very active with that industry. So then by the time I graduated from Michigan I was already thinking about doing something else. I got a job at Parke-Davis in Detroit, Michigan. Dr. Harvey Mercker was the superintendent, and he was a University of Michigan graduate and I understood that he liked to hire University of Michigan people. So I interviewed there and I interviewed I think at Ethel Corporation and I think I started work at Parke-Davis a week later. I was called to work at Ethel and my mother said- my mother who had been wondering when I was going to get a job or whether I would get one- couldn't believe that I got called like that, So I worked there for seven years in process development. And I worked on the synthesis of the first antibiotic chloromycetin. It was quite exciting. What's interesting is that the friend I mentioned before who graduated first had taken a tour of the East Coast to get a job and did not get hired. First in the class, she did not get hired. Now that's discrimination, l guess I couIdn't think of before but that's what I felt it was. Anyway, when she came back to Detroit I brought her into Parke-Davis.

KW: What was the working environment like? Were you still one of a few women?

MF: Yeah. I had a friend in the lab who was a biochemist. But we had a very congenial, great staff of chemists and chemical engineers. It was...no discrimination whatsoever (laughs). I worked in a laboratory and I worked in the pilot plant. We went up to about a thousand gallons then the production people took it over from there.

Margaret Frank, 19463

Listen to Margaret discuss her decision to have a family.

MF: Well, I got married and had a daughter who is now a pediatrician but she had asthma as an infant. And I had hard time deciding about going back to work and on top of that the department I was working for, that I would have gone back to, moved from Detroit to Holland, Michigan. So it wasn't too hard to decide, and I had married a chemical engineer.

KW: How did you guys meet?

MF: Well, actually I think I met him when I was at the junior college before I went to Michigan and got together afterwards. He was in the service and then attended the University of Detroit Engineering School on a co-op program. And we ended up with four children so I kept busy with them.

KW: So, wanting to have a family, you put career on hold a little bit to raise your children is that what you're saying?

MF: Yes. Well the first one had the health problems which was manageable...and so I raised a pediatrician, one is still going to school- he's going to get his law degree which is his third degree, and l have a daughter who is...they all went to Michigan...and graduated with a master's at Cranbrook and then l have one who has gone into library work now. So, I don't regret not going... if the company hadn't left town. I probably would have gone back.

Listen to Margaret talk about returning to work as a substitute teacher in the 1970s.

MF: Yes.

KW: What was that in?

MF: Well I was, oh it was in Secondary Education and Math. I received, because I was a stay-at-home mother involved in you know, many other things, the area we lived in was quite short of substitute teachers and knowing that I had a degree I was being urged to step in and help out. And I did that and I realized that I was being called- this was when the youngest was in school- I was being called so frequently I thought "well, my husband was traveling a great deal and we needed to have someone home, so if l could match the schedule of my children, it would be a good family choice to make".

KW: How many years did you teach for?

MF: I taught a little over 19 years.

KW: Did you like teaching?

MF: Yes I did. It wasn't as exciting as working in the laboratory. I always felt that was the high point of my career, working in the pharmaceutical industry.

Listen to Margaret describe her husband's career.

MF: Yes, natural gas pipelines.

KW: What sort of work was he doing? Did he stay in the same, with the same company? Or what was his career trajectory like?

MF: He was...he started out with Michigan Consolidated Gas in a co-op after the G.l. Bill, which provided veterans with that opportunity to go to college. And he took a job with the gas company and he ended up as Vice President of the Great Lakes Gas and Transmission Co. and he testified before FERC in Washington, D.C., figuring he must have spent almost twenty years in Washington (laughs).

Listen to Margaret discuss the lack of gender discrimination she experienced in her career.

MF: That's true. Well, when I went to Parke-Davis -and I don't think they're different now- both my friend who's a biochemist and myself -we worked in various- I was more likely to do it than she, you know, to move chemicals around and things like that. I would roll a drum and they would hire additional staff. And all of them would come in with a master's degree in engineering and say "I'm not going to roll a drum". And, not that you were rolling drums all day, it was just setting up the process, and the head of my department would say "well look at Margaret, she can handle it, you should he able to do it too" (laughs). It wasn't that they couldn't handle it physically; they couldn't handle it...their pride was hurt I guess. It was amusing because the rest of us -all the other engineers- were kind of amused by the fact that people would be reluctant to do some of the parts of the work that were really just a small part of the process of putting things together.

KW: So overall, you'd say it was a pretty positive experience?

MF: Oh definitely.

KW: You mentioned your friend who went down the East Coast looking for jobs and couldn't get hired, why do you think that was? What was the difference between the East Coast and Michigan where you were hired so quickly?

MF: Well, I have no idea of their hiring practices on the East Coast. I just figured a lot of Ivy League Schools were supplying their laboratories. I don't know, I never really gave it much thought. I just felt it was the discrimination.

Margaret Frank, 19464

Listen to Margaret describe her children's, niece's, and nephew's careers.

MF: Well it was very odd, my Ann Arbor daughter went and got her degree in arts and she had toyed with the idea of going into chemistry so that's it.

KW: Yeah, that's the closest you got.

MF: Well, to tell you the truth we have...my children are part of a group of cousins and five of them are physicians, three of them are lawyers. and it's more or less...not competition but they don't want to just follow the same field. They want to stand out as individuals. And they're all Michigan and Michigan State graduates...all except one.

KW: Where did that one go?

MF: Oklahoma.

Advice

Listen to Margaret's advice to women who want to pursue engineering.

MF: Well, they need to be self-reliant and really like what they're getting into. And their background interests...they've really got to have strong math and science background. But I think creativity is really very important and that doesn't seem to be stressed a great deal. But I've found that always asking questions- asking questions (laughs). And question the status quo or what you think is being perceived as the status quo. Well, I recommend it. But I never tried to affect my children's choices. So, ideally you have to do it because you want to do it not because someone else is urging you to do it.

KW: That's a good attitude to have, definitely.

1. Michiganensian, 1937, p. 101

3. Margaret Frank, 1946; from her personal collection

4. Michiganensian, 1946, p. 205

Women In Science and Engineering

1140 Undergraduate Science Building

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

ph: 734.615.4455

e: umwise@umich.edu